#Hopchytsya

Kolya languidly leads a horse harnessed to draw a cart. Spotting a headscarf or locks of hair behind a fence, he shouts from afar:

“The journalists are here to write about you!”

Having barely heard his cheering cry, the people hurry back inside their homes.

“They should be glad that someone talks about them, not run away!” Kolya shrugs. He is in his 50s. A jacket hides his lean body, while a cap covers some bald spots on his head.

Ukrainian war veteran Roman Leonidovych and Kolya walk down Kooperatyvna Street, which has its turn to collect food supplies for the East before the Easter. Each year, the volunteers in Hopchytsya send help to the forefront on three separate occasions. Roman Leonidovych went to the war twice: first with the National Guard near Popasna and Krymske, and then as a soldier in the Armed Forces of Ukraine near Hnutove and Talakivka.

The street is narrow and winding. Cherry and apple trees are in bloom in the courtyards, and the wind carries white petals throughout the village. Malysh, the horse, grazes by the side of the road. Glass jars clatter, potatoes roll out of a sack, and Kolya quickly puts the food brought by the villagers back in its place.

One autumn day, his sick confused mother left the house. In the spring, once the snow melted, they found her body in the woods. A year and a half ago, Kolya also lost his wife. Later, both of his daughters moved to Vinnytsia, so now he lives alone. Three empty houses are looking into the street with their azure windows—traditional for Hopchytsya.

The gravel crackles under the wheels. We make a stop on the corner. From the house at the intersection waddles the old Halia, clutching a tidy bag of peas, rice, and jam. Apologizing profusely for not having potatoes or eggs, she puts what she has on the cart, gives Roman a hundred hryvnias, and goes back to her house dejectedly.

Her son, drunkard Hrysha, pops out of the next gate. His eyes are glassy, his skin is waxy, and we can hear just a few individual words between swearing. He approaches the cart, looks surprised at the camera and tries to take the bill out of Roman’s hands—he is used to booze away his mother’s money. Leonidovych and Kolya both blush.

Suddenly, a cultured-looking man wearing glasses appears as if out of nowhere.

“Get out of here, Hrysha! I’ll buy an Easter sweet bread for the boys with that money,” Mykola Zakharovych says authoritatively—he looks like a European retiree. People call him Zakharovych. This will be his twelfth time taking Easter gifts from Hopchytsya to the East.

Hrysha shuffles off. Old Halia watches him helplessly behind the nearby fence.

Done with Hrysha, Zakharovych lively instructs Roman and Kolya on where to bring the collected food. We move on—past the houses of Larysa who moved here from the Zakarpattya region, of Oksana, sister of the head of the village council, and of the newcomers from a neighboring village who had quit drinking in Hopchytsya after finding jobs.

“We don’t drink here much. It’s mostly the young,” Kolya says apologetically, urging Malysh forward. “Hyah! Hyah! If they have no jobs.”

He goes silent for a minute, and then adds:

“We have a monument to the soldiers here. A bottle of vodka was mured in the helmet!”

Kolya laughs and turns to the paved main street. He points at the villagers in a ploughed vegetable garden by the road.

“That guy was in the ATO (Anti-Terrorist Operation, the Ukrainian government’s operation in the War in Donbass, 2014–2018 — R.). He was a de-miner. Now he owns a tractor and grows potatoes.”

In total, fifteen men from Hopchytsya went to the war. All of them came back, none were wounded.

Like Berlin

We make a stop by the lake for Kolya to show us the swans. While the birds smoothly land on the water as if on cue, a woman called Halia cheerfully emerges from the last house on the street. She is bringing two large jars of tomatoes, casually talking to a neighbor behind a low fence.

When she retired, Halia took up embroidering. She makes pillows, towels, and napkins and gives them to her grandchildren and guests. Having lost count of all her embroideries, she still counts the pillows—so far, she made 68 of them. She says she has embroidered a portrait of Taras Shevchenko for the office of her son—head of the village council Roman Prylutsky. In the 2015 election, Roman beat his predecessor, who had served three terms. In the past, he would not even attend community meetings, but having turned head of council, quickly got the hang of it.

Two decades ago, Roman went to Germany with his fellow villagers as a migrant worker, “to make renovations.” He still has dreams of Germany. Over the six months he spent in Berlin, Roman was most impressed by two things: neat forged fences and people carving out their lives without ruining the lives of others. Roman tries to implement his German experience in his native Hopchytsya.

Before taking the office, he worked as a welder at a local poultry farm for 15 years. He forged most of the fences in the village with his own hands—it is easy to identify his work between wooden and tin gates by colored flowers and curls. These days, he has abandoned forging.

“Once I was elected, I’ve had no time for the hobby. The salary is lower than that of a welder, but I want Hopchytsya to become more like Berlin.”

A relative of Roman—Sashko who’s now living in the capital—suggested creating a website and the village’s profile on social media. For the last four years, they have been Hopchytsya’s trademark. Roman sends him news and photos, while Sashko manages the online life of the village. He also looks for archive documents, publishes articles on the history of the village, and keeps track of statistics. Today, even Ukrainians abroad read about Hopchytsya.

Roman spends little time in his office: he has to clear out the trees taken down by the storm, check on the progress of the renovation in the community center, make sure the waste collection point (like the one he saw in Berlin) is open, see if the crisis families have received their money, whether children go to school, whether a new border was drawn between the land plots, whether roads are being repaired properly. People often stop his car and ask for advice, complain or suggest something right through the open window.

The villagers give Roman most credit for the events here: the ice hockey championship, the Kupala Night celebrations, Easter egg painting master classes, bicycle races, communal work, and the many fairs that have taken place.

“Not a single penny was spent on this from the local budget: craftsmen volunteer, local farmers help with money, Hopchytsya bands perform at concerts,” he says proudly.

Still, some people are displeased. They say he plans a lot but does nothing. Playground building projects, putting up lighting in all the streets, completion of construction works at school, road repair. . . The village has the money, but where is the result?

“Hopchytsya’s budget is UAH 1.3 million ($56,000 — R.), but after payment for utilities, barely UAH 400,000 ($17,000 — R.) is left for the economy management. Over four years of my term, this number has remained almost the same, because it is replenished through the sale and lease of land, which is limited in the village,” Roman explains.

The school is the main and most expensive challenge for Hopchytsya. Children have to study in the old building dating back to the 1920s, while the unfinished building of the new school has been abandoned since 1989. There are walls, the roof and windows, but the construction was frozen when the Soviet Union collapsed. To complete the construction, the village needs UAH 77 million ($3.3m — R.), of which one local farmer is willing to put up UAH 7 million ($300,000 — R.), but Roman has no idea where to get the rest.

He dreams of finishing construction works at the school and moving the kindergarten there, of opening an outpatient clinic in its place, of repairing a library, a center for children’s hobby groups, of giving more space to a private dental office. He dreams they will manage to build a waste recycling plant and there will be no landfills around the village. He dreams that more people will help out with communal work. And most importantly, that the village will be a nice place for both locals and tourists.

Hopchytsya is located by a mountain range where granite was mined in the quarries from the 1930s until the 1990s. Shortly after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the pumping machines stopped. The village cannot resume the operation—doing so is not in its powers. Instead, it can offer tourists two scenic flooded quarries.

The quarry closer to the main road is shallow, up to 14 meters deep. The streams that flooded it washed away the sandy soils, so the water here is of a delicate terracotta color. Apricot trees cling to the rocky cliffs, and human-sized boulders are scattered around like some giant’s granite toys. The second quarry is almost a hundred meters deep. The water is clear, almost azure in the sun.

To promote the granite attractions, Roman invited artists to paint them. But instead of boulders scattered with blasts and abandoned mining equipment, they painted the surrounding landscapes. Some of their works are exhibited in the museum, which is run by local amateur historian Misha.

Misha

Mykhailo Dmytrovych, or just Misha, knows almost everything about Hopchytsya. He can tell about the places visited by Shevchenko with an expedition, where Honoré de Balzac once stayed, where the old water mill once stood, where Russian counts and diplomats used to live, who and when found the silver coins of Sigismund III Vasa, where the former Ros riverbed once was, and how Tatar incursions are connected to the name of the village. One can listen to Misha for hours.

The Hopchytsya Museum he manages is located in the former dining room of the collective farm, decorated with recovered and somewhat broken Soviet stained-glass windows depicting metallurgists, workers, and soldiers. Enlarged copies of the old photographs of the Hopchytsya residents are hanging on the walls: people used to get photographed at the parlor in Pohrebyshche, so every photo has a plastic palm tree, which was exotic for the 1930-1950s. Roman’s grandmother is leftmost, sitting barefoot.

The locals give the museum what they mostly do not need themselves: millstones to make a monument to the victims of the Holodomor; a spinning wheel, which still has the non-woven hemp cloth left untouched since the beginning of the last century; rusted sickles and shovels; shoemaking machinery; old embroidered shirts and overcoats dating back to the end of the 19th century, which were used by almost half of the village for “kolyaduvannya”—Christmas caroling; old 1894 icons and memorial books telling the history of the village church; photos from the villagers since the 1920s when they opened the school. Misha collects everything with care. The museum has five rooms, displaying the flint knives of Trypillian times and the glass ironing ball, the incendiary arrow of the Kievan Rus times, a piece of meteorite and the melted sand from a crater near the village, some old money that someone tried to steal once.

Misha became a museum worker quite recently. He has a degree in ichthyology and used to work at a local fish farm for a long time. When Ukraine became independent, he was a stock manager at the state postal service for two decades but was laid off after its reform. Misha could have remained unemployed, but he came in useful at the museum.

“We study the history of the village, look for something interesting in other museums, check the stories told by the old-timers. As long as we have interesting exhibitions, people will come to us,” Misha starts playing a record by his beloved Mark Bernes on a museum phonograph, which he will later lock up in the safe.

The record creaks, its sound barely audible, as if dusted. Misha listens out, and his face lights up.

Culture In for Repairs

As soon as social media profiles were set up for Hopchytsya, various media wrote enthusiastically about the village because of its Wi-Fi and local bookcrossing. Roman shows the booth by the community center, where books, tapes, and CDs were kept back in the day. The days of bookcrossing are over, so the booth will be relocated to the stadium.

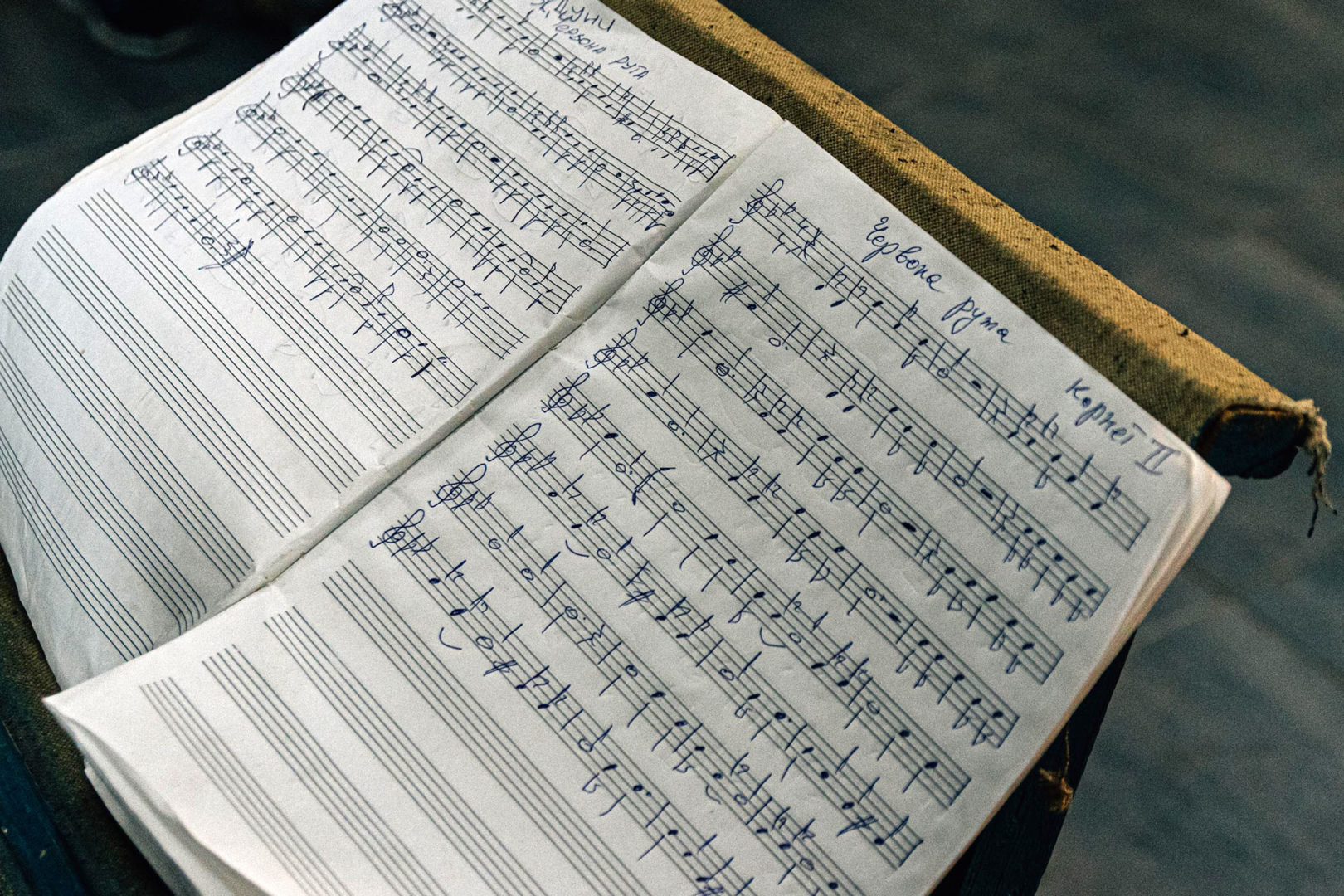

The community center is still under reconstruction: the assembly hall, the fitness room, the gym are already finished, but they are yet to repair the roof and finish the library. Dance parties usually take place there on weekends, and on weekdays, after school, local boys play in the brass band, led by Oleksiy Labenko—director of the community center.

“We used to have an orchestra of 24 musicians, and even a soloist! They were invited to play all across the region. And now everything is gone. . .” says Oleksiy. A member of the brass band in the orchestra in the 1980s, he is nostalgic for the Soviet past.

To revive the Hopchytsya orchestra, Oleksiy gathered 9-12-year-old schoolboys to play wind instruments and drums. It is now the only children’s orchestra in the Pohrebyshche district, and the boys represent the village at festivals and fairs. There is no money for the new instruments, so they had to scour throughout warehouses and surrounding villages for the old ones. The oldest instrument is the 1963 bass, which is 45 years older than its player.

The boys diligently puff their cheeks, looking at the handwritten sheet on the music stands dated back to the times of Oleksiy’s nostalgia. Blue as the windows in Hopchytsya, the stands are covered with old linen.

“That’s it, you still have homework to do,” Oleksiy says, calming down the enthusiasm of the young musicians after Chervona Ruta (a biennial all-Ukrainian youth festival of contemporary song and popular music — R.).

But the boys are in no hurry to leave. They stay to play chess, also habituated by the musician.

“We hold all concerts on our own. Children sing, dance, recite poems. We always have a full house,” Oleksiy says proudly, gathering the instruments.

As darkness falls on Hopchytsya, the kids run outside and fool around. Drummer Artem gets on his bike and, five minutes later, comes back with a ball. The exhausted sun lingers on the fields, where it seems the joy of childhood itself is running around.

The Saints Under the Roof

In the 19th century, a Serbian merchant Ivan Riznic, who was friends with the Russian poet Pushkin, lived in Hopchytsya. He built a church, which was dismantled by the Soviet authorities in the 1920s—its timber was re-purposed to build the school. In the days of the Soviet Union, the locals forgot about the origins of the timber. One day, while repairing the building, which was in critical condition, they noticed the beams covered with paintings and icons in the attic. When Roman took the office, he vowed to save them and started looking for restoration artists. Having heard about the paintings, a local priest Father Ivan and I come to see them.

The Principal has gone to Pohrebyshche for a meeting. The Deputy Principal Halyna Ivanivna has been ordered not to let anyone near the roof. To any questions we ask her, she smiles and keeps saying:

“I know nothing, I am new to the school.”

Having no luck with the school authorities, we call Roman. Later the Principal calls her Deputy. Halyna Ivanivna turns gloomy and orders the groundskeeper to put a wooden ladder under a metal hatch in the ceiling.

The wooden roof is covered with tightly adjusted metal sheets. Not a single beam of light works its way into the attic. The light of the torch picks up pillars of dust from the darkness. The attic floor is caving in, but the groundskeeper moves steadily and quickly finds the wooden beams, from which Virgin Mary and the saints displaced to the school roof look down at the intruders with their peeling eyes.

Seeing the open hatch, the children peck their heads and hold their breath: who will get out of there? The little ones pester us about the attic. “Is this how you are supposed to behave at school?”, “Go back to your class!”, “Be quiet!” the teachers scold them. Most kids toddle off down in the mouth.

School authorities let out a sigh of relief when we go back to the car. They dislike Roman with his “reforms” and fear that due to the possible merger with the large community of Pohrebyshche, the school in Hopchytsya will be closed.

“Roman is young, energetic, tells everyone about these beams. He was the one to launch the website and profiles on social media. And the Principal is “old school”—no one is allowed, everything must remain as it is,” the priest says with a shrug.

In Hopchytsya, the school is more conservative than the church.

***

Zakharovych—“European retiree”—is getting ready to take the tributes from Hopchytsya to the East. Tobacco from a local farmer and a box of eggs from a poultry farm are added to the food brought by the villagers.

Zakharovych is 70, but he is jovially loading up the trunk.

“I used to live in Kyiv, and when I retired, I went back home. This place was calling me back. What would I do in Kyiv? I would live on the tenth floor of an apartment building and play dominoes in the yard. And this place is full of life,” he pauses, sighs deeply, and looks at the field spellbound.

We go to see the communal work, where people clean the central street of the village. There are only a few volunteers. Roman Leonidovych tells several men who gathered around Malysh’s cart about the war.

“The time has stopped there. They are lost and deluded,” Roman leans on his shovel.

Everyone is silent.

He returned to Hopchytsya because he broke his arm in a trench. He will go back soon.

Roman gets to scraping the grass off the pavement in silence. The rest also get back to work—there is no time to talk, as they have to clean the street by nightfall. Malysh, the horse, quietly pulls the cart along the main street.

[This publication was created with support of the Royal Norwegian Embassy in Ukraine. The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Norwegian government.]

Have read to the end! What's next?

Next is a small request.

Building media in Ukraine is not an easy task. It requires special experience, knowledge and special resources. Literary reportage is also one of the most expensive genres of journalism. That's why we need your support.

We have no investors or "friendly politicians" - we’ve always been independent. The only dependence we would like to have is dependence on educated and caring readers. We invite you to support us on Patreon, so we could create more valuable things with your help.

Reports119

More