The Earth Gave, and the Earth Has Taken Away

In 2010-2018, 315 miners were killed in Ukrainian mines. In the first half of 2019, six more people were killed. Nearly 12,000 were injured. The Ministry of Energy and Coal Mining shares statistics only for the last ten years. Allegedly, there is no information for the previous years.

The MiningWiki encyclopedia for miners has been collecting data on mining accidents in Ukraine since 1992. It reports 906 deaths. Those who were killed left wives, children or parents behind. The mine gave them a job, but it took their lives in return.

Despite the high mortality rates, Ukrainian mines continue to operate, and each year hundreds of young professionals graduate from the country’s mining colleges and universities, willing to go underground again and again.

Liudmyla Vladyk, widow of Volodymyr Vladyk who died in August 2014 in the Pavlohradska Mine (DTEK)

Liudmyla Vladyk opens the gate and invites me to sit down on a bench outside her house. She’s just back from the veggie garden. She is a stay-at-home mother looking after her younger disabled son. The two live with Liudmyla’s mother-in-law in her private house in Pavlohrad, Sicheslav region.

Liudmyla’s husband Volodymyr died during his shift at the Pavlohradska mine five years ago due to cardiac arrest. After his death, the widow decided to rent out the flat where they used to live, because everything there reminded her of him.

“He was buried on Miner’s Day—the most important holiday in our family. Everyone came to terms with it, dealt with the pain. We can’t change anything. That Friday night, my husband worked his fourth shift. Saturday morning I was working and was in good spirits. And then I got a call that he was dead. And we had just stocked up to celebrate Miner’s Day. For us, this holiday was like Christmas or New Year’s. We haven’t been celebrating it for five years now.

“Although Volodymyr never complained about his heart, on his fourth shift he was taken out of the mine dead. His death came as a shock to everyone. My husband had a clean bill of health, and never paid doctors under the table to get a medical fitness certificate. His blood pressure was 120/80. Yes, he had back issues, chronic bronchitis, but these are common health issues among miners.

“He had been working as a team leader at the Pavlohradska mine since 1999. We met when he was going home from the very same fourth shift, and I was selling ice cream. He stopped and we got to talking.

“I was 19 and he was 24. After three months of love, we got married. I still cannot understand how we could get married in just three months. We had our first son a year and a half later. Ten years after, our second son was born. Of course, he lived for us and for our sake, took us on vacations, did everything for the family.

“The mine paid for the funeral and for the tombstone. On the anniversary of his death, his teammates brought me some money. He must have been a good friend to them.

“There was an investigation after the incident, and I was invited to the meetings with the commission. They tested him for alcohol and drugs but found nothing. Once the expert examination was over, they gave me the documents. I keep them. Maybe they will help my kids somehow.

“The eldest was admitted into university last year. He got in without any help, getting a scholarship and not using the death of his father as a way in. He studies at the Mining Institute, the Faculty of Earth Sciences. But he said he wouldn’t go into the mine. He said his Dad had had enough of it.”

Olha Kushnarenko, widow of Ruslan Kushnarenko who died in May 2013 at the Blahodatna mine (Pavlohradvuhillia Enterprise, DTEK, Dnipropetrovsk region)

Olha Kushnarenko also lives with her mother-in-law and calls her “dear mom”. Together, they bring up her son—eight-year-old Artem.

Olha has pink lipstick on her lips and is holding a purse in her hands. She invites me to sit in her Lada 110 to talk. The car doors are open—it’s a hot summer day. Dogs are barking and neighbor kids are playing nearby.

I can feel that it has taken her a while to put herself together and learn to keep back her tears. But the tenuous, thin barrier crumbles down as soon as we start talking about her husband. There come the tears and the conversation fills with long pauses.

They met at a bus stop. Olha was working as a packer at a crouton factory in Synelnykovo. One evening, she met her friends, and they got to talking. Ruslan got off the bus and asked for a phone to make a call since the battery on his own phone was dead. The girls agreed to help for a chocolate bar. This is how they met.

“My husband was working as a mining electrician at the Blahodatna mine. On May 22, 2013 he went to work for the last time.

“He left in the morning and never returned. We were waiting for him till 4 p.m. I thought he was just running late—sometimes the mine shuttle buses leave later than scheduled. All our neighbors already knew what happened, but nobody told us.

“Finally, someone from the Blahodatna called us. They said: ‘Please, keep calm, but there was an accident at the mine.’”

On that day, at the end of the shift, two coal-filled trolleys turned over in the 143rd mother entry on the 210-meter horizon. They killed two mine electricians. One of them was Olha Kushnarenko’s husband, thirty-three-year old Ruslan.

“The trial against some of his teammates who were working underground that day is still ongoing. None of the management was charged or dismissed. I was attending all hearings and studied all volumes of the case, and personally I don’t think these guys are guilty. If the mine observed health and safety rules, if the working conditions were adequate, there wouldn’t be such accidents. The mine must be equipped so that people get back home alive.

“I haven’t met those guys before the trial, but my husband told me about them. I knew their last names and what sort of people they were.

“I remember the investigator asking me if anyone could deliberately tamper with those trolleys. What nonsense! Those guys could have been in Ruslan’s place.

“In the end, I did not carry on the lawsuit, I waived my claims, stating that I have no complaints. I was told: ‘You must have been paid for that.’ That’s not true.

“My husband’s teammates, and there are more than twenty of them, come every year. We go to the cemetery together. They are regular people. Their foreman is innocent. He also has a family. One of the defendants had two children born during the investigation period. I can’t imagine how his wife coped with the stress during the pregnancies…

“My husband was such a kind person. He wouldn’t want me to bring his friends to trial. How could I? I feel sorry for them. They told me how they rushed there when the accident happened; they wanted to help. But it was already too late.

“The trial must be still ongoing because the wife of the other miner who was killed is seeking compensation of non-pecuniary damages.

“Ruslan was a good man. I wish there were more people like him. Our son wasn’t even two when his father died. I have my husband’s photo at home and we go to the cemetery often. I told Artem that his daddy is gone, that he is in heaven and looks down at us. I did not tell him that he was killed in the mine. He looks at the photo and says: ‘My Daddy’. At the cemetery, he kisses his tombstone. He loves him in his own way. He just finished his first year at school. He’s so grown up and looks just like his Dad.

“When I was giving birth to our son, my husband said he would name the boy. When he came to the maternity hospital and was holding the baby in his arms, I reminded him that the boy still had no name and I was just calling him ‘son’. I used to tell him before that I liked the name Artem, so Ruslan named him that. He wanted this baby so much.

“My husband and I lived together for only three and a half years, but they were happy years. We bought a car, had our son—life seemed to be good. I never thought everything could end so quickly.

“I still can’t believe it. At first, I would imagine that he was just hiding somewhere. Or that there was some mistake. ‘Maybe it’s all a lie?’ I thought. Because I never saw his body—my godmother went to the identification. Mother and I wouldn’t have been able to handle it. They told us right away that there was nothing left to look at. Godmother came back and said that she’d never tell us what she saw.”

Tetiana Kolida, widow of Taras Kolida who died at the Stepova Mine in March 2017 (Lvivvuhillia State Enterprise)

Chervonohrad is a mining town 70 kilometers outside of Lviv. Here, life has its special pace. At 4 a.m., lights turn on in the windows of the apartment blocks. At 6 a.m., old LAZ and Ikarus buses with mine numbers on their windscreens are shuttling miners around town. In total, there are 7 mines in Chervonohrad and its suburbs. One way or another, most locals are involved in their operation.

Tetiana Kolida lives in the village of Pozdymyr. She works as a paramedic at the village’s medical station, raises two kids and is finishing the construction of the house that her husband Taras and she started building some time ago. Now she’s at it alone—Taras died in the mine.

On March 2, 2017, there was a rockslide in a conveyor belt at the Stepova mine in the village of Hlukhiv, near Chervonohrad. 34 miners worked at the dangerous section. Eight were killed, including Taras Kolida. It was the largest accident in the history of the Lviv-Volyn coal basin.

I meet Tetiana at the bus station. She is a blond-haired cheerful woman. Her black t-shirt says, Do Not Disturb. She is sensible and calm when talking about her husband, but after a while, she willingly releases her emotions.

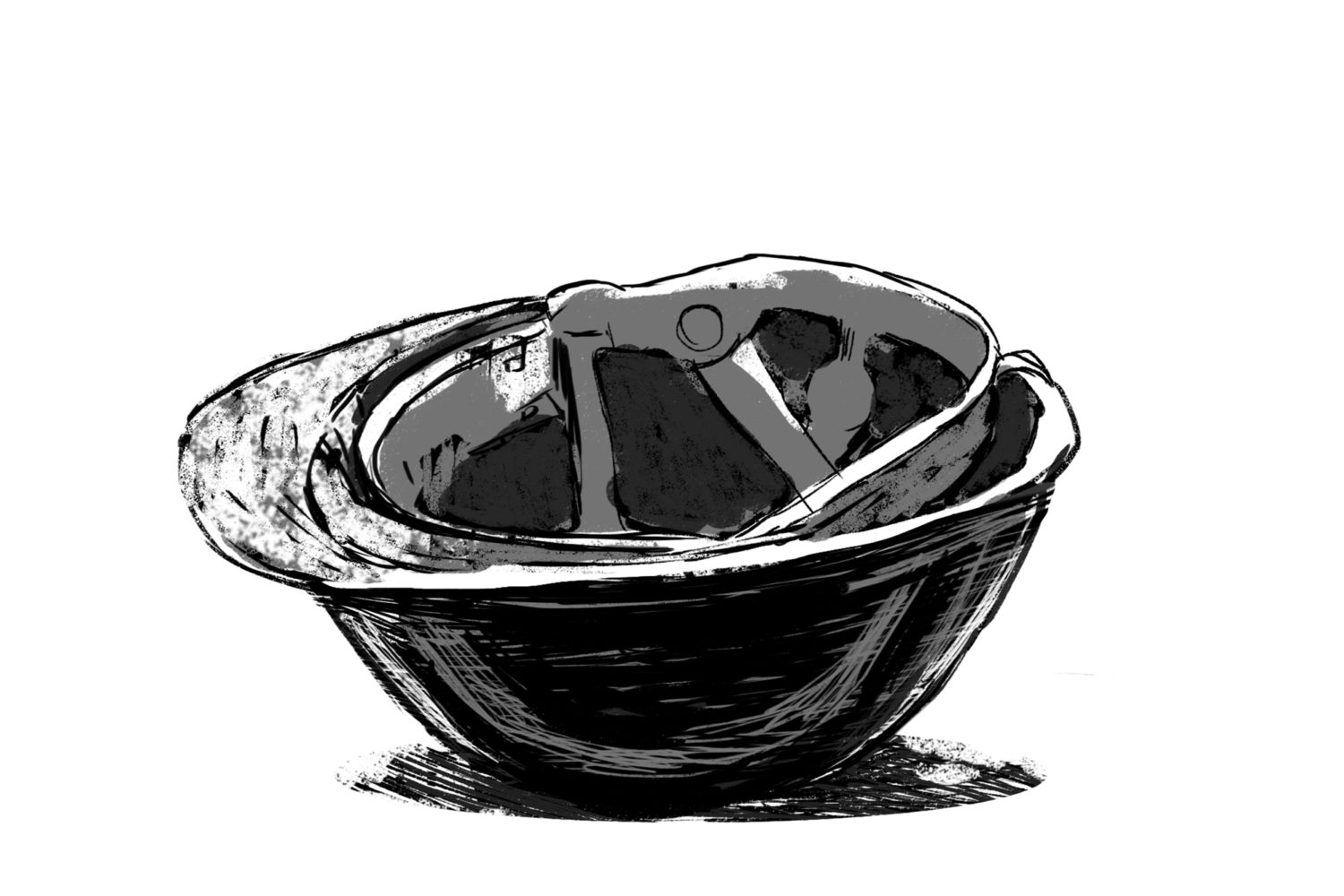

“It was the first shift. Getting ready for work, he told me to turn off the lights, because electricity prices went up earlier that month. As always, I prepared his lunch box. Gave him a goodbye kiss.

“After work, Taras had to drop by the store in Chervonohrad to buy some food, but I got a call from a nurse who said there was an accident in the mine.

“For me, an accident in the mine is when a combine breaks down and they don’t get paid. Or when the steam loco is stuck, and they won’t get paid for that day because it needs to be taken out. Anything but what happened.

“On that day, somebody asked me to help a local woman who felt ill. She kept saying: ‘What will I say to the kids?’ And I still had no idea what it all was about. I thought her husband was some manager, and she was worried about him. I believed that it’s the management who was first and foremost held responsible for accidents.

“Then I took my first aid kit and we went to the mine. Nobody was waiting for us there. They weren’t telling us anything and didn’t let us in beyond the checkpoint. But seeing high-rank people arrived, we could figure out the scale of the accident. Groysman was already giving a press-conference in the headquarters, while I was still unaware of what happened to my husband.

“I saw his teammates coming out from the shift, so I asked them if they saw him, but nobody could tell me anything. I kept looking at my phone: no calls. My husband told me earlier that he had put my phone number in his insurance, so they could tell me if something happened. So, I thought that they would have told me already if there was something wrong. His parents called and said Taras was gone. ‘How can you know being in the village? I’m here at the mine and nobody says anything,’ I asked them.

“Until a friend came out and said: ‘Stay strong, your husband is on the list.’

“We went to the Chervonohrad hospital. It’s 15 kilometers away from the mine. There was an A4 page with a handwritten list of names of those who died. By that time, we had downed so many sedatives that our reaction was slow. I couldn’t figure out what to do next and how I got there. I said goodbye to him just that morning, and now my husband was no more, while I was left alone with that piece of paper.

“Later I asked at the HR office why they hadn’t called me. They said they were at a loss.

“It’s hard without my husband. I can’t do many things alone.

You feel the loss every day. When husband was home, I went to bed and felt much safer. I felt sure of our children’s future. And now there is a house, but there is no man of the house. We bought a car, but there is no driver. There are children, but there is no father. There are old parents, but there is no son

“On kindergarten graduation day there’s a father-daughter dance but there is no father. Everyone is taking Easter cakes to church with their husbands, but I am alone. Everyone gets together with their families for dinner, and I am alone.

“Taras and I discussed that he should leave the mine because it’s dangerous. He went to work there because we needed money to build the house. Before that, he was working as a forester. But my husband would say: ‘You don’t even imagine what a well-balanced system a mine is.’ And yes, working there was dangerous, but there they were all for one and one for all—like a big family. ‘There is an entire Ministry of Coal Mining. University-educated people go to work every day. They care about our safety.’

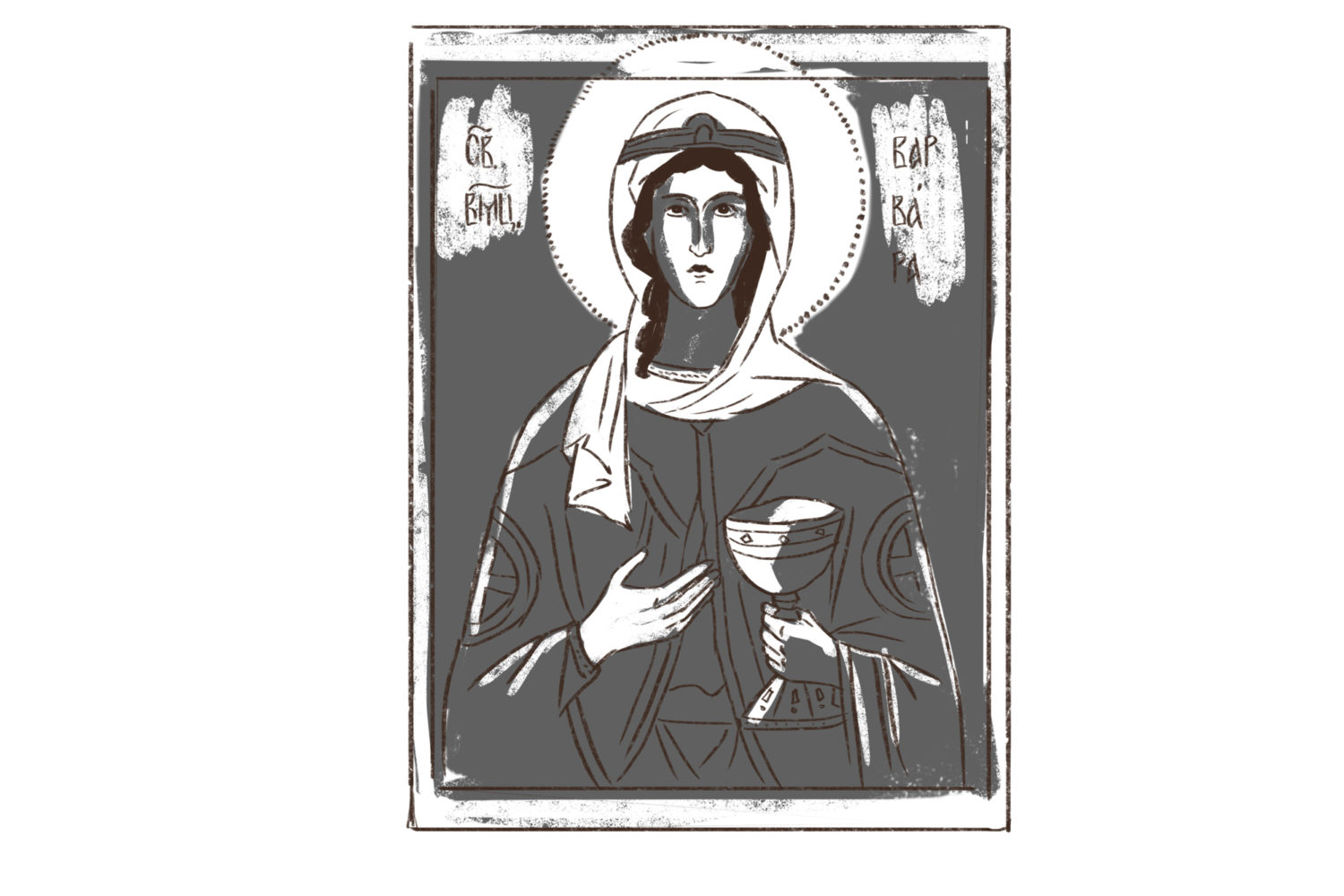

“Taras was very pleased to have been born on December 17, Saint Barbara’s Day—the patron saint of miners. ‘We enter the mine, and St. Barbara meets us,’ he used to say. For seven years there, he had not had a single scratch. It’s a hard job, and I often see mine workers at the medical station with bronchitis, bursitis, and back pains. Wall blocks fall on their heads. But my husband believed St. Barbara protected him.

“The kids struggled to handle this loss. We agreed with them to think that dad went to work abroad. If we behave well, he would send us something nice. My son wanted a basketball ring so much, and Taras promised to make it for him a long time ago. So we bought it and set it up. He was so happy. And the kids started believing our story, and I did too. It’s easier to live that way. As if he would come back or call us some day.

“We became friends with the wives of the other miners that were killed. Seems like they are the only people who really know me. I catch myself thinking that I didn’t understand widows before, because I saw strong, self-sufficient women. But nobody sees how much effort it takes.

“It’s been two years now, and there hasn’t been a trial yet. After the accident, they promised us a lot, but no one was punished. Some people got promoted, others keep working as before.”

Halyna Klak, widow of Oleksandr Klak who died at the Stepova Mine on March 2, 2017 (Lvivvuhillia State Enterprise)

Halyna Klak’s husband Oleksandr died together with Tetiana Kolida’s husband at the Stepova mine. The women did not know each other before the accident—their loss brought them together. Halyna is a dark-haired and slim woman. Her eyes carry endless fatigue and sadness.

She met Oleksandr in Lviv. He had been a miner for a long time, and after they met, he took her to Chervonohrad.

“It was so fast. Our life together had just begun, and suddenly, I was alone with a little child. I didn’t know what to do. We lived together for only three years and four months.

“That day, he went to work as usual. And then someone called me and said there was an accident at the mine. My father-in-law built that mine and worked there for more than 20 years. My husband’s mom worked there for a while too. So when we came there, they let us in right away.

“I kept asking if anyone knew what happened to Oleksandr Klak. Some woman told me: ‘I don’t know how and what to tell you.’

“And then they opened the door to the medical station or something like that and I saw covered bodies inside. They were lying right on the floor. ‘What is that?’ I asked. They let me in to look. I had to come face to face with death. The dead were taken up dirty with coal. My husband’s father went to identify his son amongst the killed, so that I didn’t have to do that. But I didn’t believe him—so they showed him to me as well. Now I have to live with it.

“A special investigating commission worked for a year. The bill of indictment taken to the court mentioned six people involved: acting director of the mine, occupational safety engineer, chief engineer, and three site managers. In the Sokal court, the case got to a judge whose commission was expiring. And the new judge studied the case for more than half a year. When we came to the appointed hearing in July, there was no judge—he went on vacation. On September 26, a preparatory hearing was held. So there hasn’t been an actual court hearing yet.

“After the accident, I decided to continue my studies. I already had a degree in management, but wanted to get a law degree to be able to protect myself. In 2017, I became a student at the Lviv University of Internal Affairs. It gave me strength. I switched to something new and met new people instead of locking myself up in the house and grieving. Now I realize that it was the right decision.

“My son wasn’t even talking yet when my husband died. When he grew up a little, I told him that his daddy was gone and would never be back, so that the kid doesn’t wait for him. I couldn’t say that his daddy was buried in the cemetery; I didn’t take him there. We just live without a dad.”

***

The widows of miners feel worn out. For some of them, even anger ran dry.

St. Barbara took their men to heaven and is now looking after the others.

For no one else does.

[This publication was created with support of the Royal Norwegian Embassy in Ukraine. The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Norwegian government].

Have read to the end! What's next?

Next is a small request.

Building media in Ukraine is not an easy task. It requires special experience, knowledge and special resources. Literary reportage is also one of the most expensive genres of journalism. That's why we need your support.

We have no investors or "friendly politicians" - we’ve always been independent. The only dependence we would like to have is dependence on educated and caring readers. We invite you to support us on Patreon, so we could create more valuable things with your help.

Reports119

More