The Stamp They Knew Me By

Like a ghost, “he” lives mostly in memories: collective, abstract, faceless. “It was a very closed environment,” “you won’t find anyone alive now,” dozens of people will say.

Likewise, you won’t find the line “confiscation of souls to an accordion” in Lina Kostenko’s 1977 collection, or “censor MB32617” in Yuri Andrukhovych’s army story.

They say “the censor didn’t allow it,” “the censor cut it.” Where is this “someone” who caught words like fish, pulled them out like teeth? Did he ever, perhaps, feel sorry for these words?

It seems now like no one can really remember. It’s like the censors have vanished without a trace, just like the words cut from the books.

I want to find these people.

***

The fourth floor, an uncertain step, trembling, and a suddenly subdued voice: “Here you are. . . for review. . .” And then off like a shot, out of the office where two people sit unmoved, a small dark man and a curvy woman.

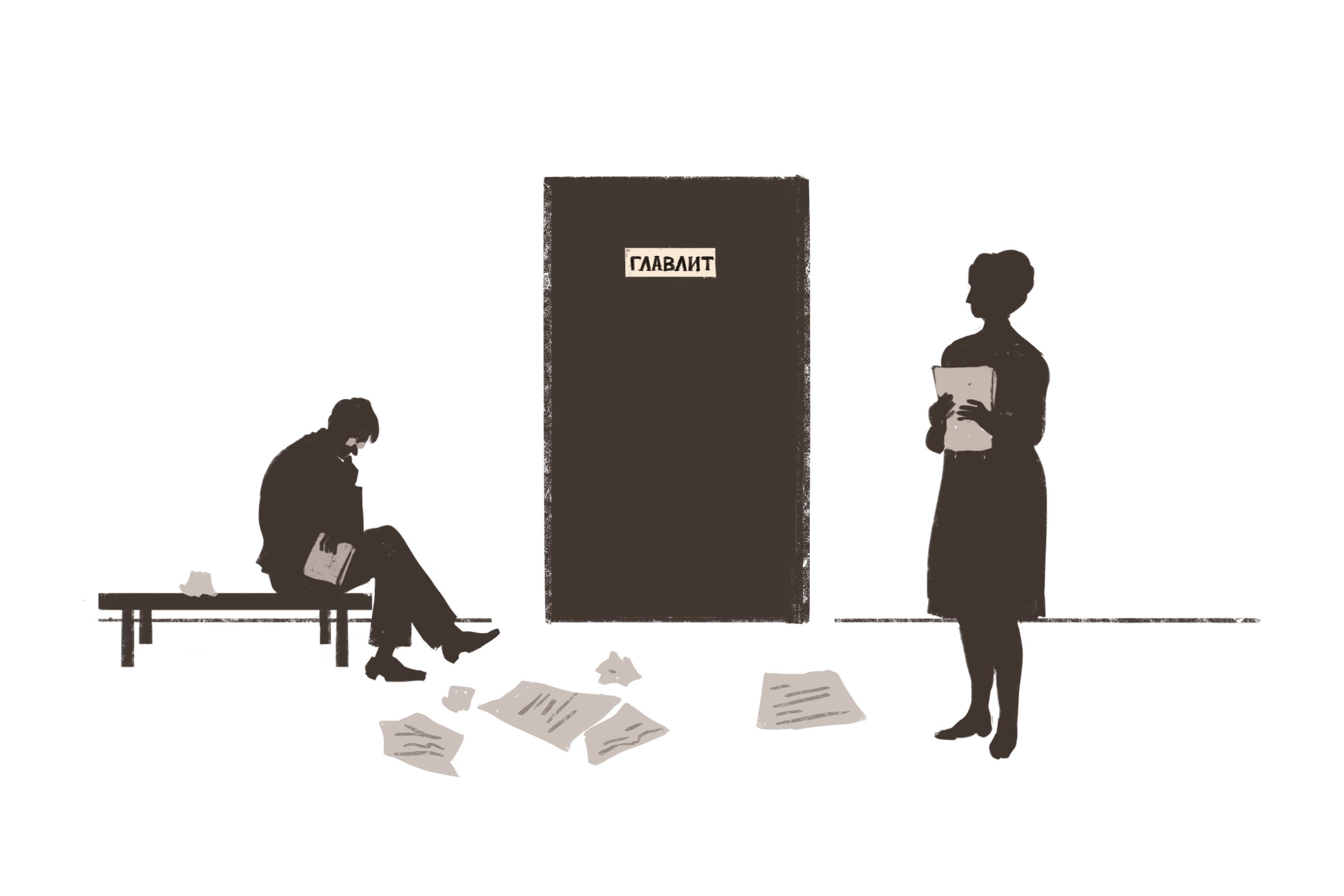

Thirty years have gone by and Olha Martsypan has forgotten a lot, but the door and sign “Ho-Lov-Lit” (Holovlit was the Ukrainian abbreviation for the official censorship and state secret protection organ in the Soviet Union — R.) on the fourth floor of the Soviet School publishing house (known today as Education) she remembers like it were yesterday.

“The junior editor was like a secretary!” Olha, emotional and cheerful, rushes to tell me about her work. “Once a book went to press and everything was ready—the artists had signed off, the editors, the correctors, the economists, absolutely everyone—the book had to be handed over to the fourth floor. And there was that door! And that sign!”

It wasn’t just Olha who quivered before the sign on the fourth floor. As she recalls, back then everyone in the publishing house did. Because if anything forbidden was found in the book, it would be returned. They would have to do everything all over again. And although Olha doesn’t remember any such incidents (after all, these were not the worst of times), there were legends running around the publishing house about an editor who was fired after allowing an “incorrect” poem about Lenin.

“Beware!” the old-timers warned those like her.

Just who was working behind that door with the Holovlit sign, Olha says, no one knew. Neither their last name, nor their first. They were not a part of the team nor the publishing house staff. They did not show up at meetings or celebrations. The curvy woman wouldn’t even say hello when she ran into someone in the bathroom.

Where to look for these strangers from the fourth floor now, Olha Martsypan does not know.

***

The inscription “Ho-Lov-Lit” (which Olha still divides into syllables and before which she once trembled) meant the branch of the Main Administration for Literary and Publishing Affairs. Holovlit was founded in the Soviet Union in 1922 and over the next 70 years decided what the Soviet people would read, hear, and see.

This spooky bird had two wings. One was political—it kept state secrets (information about the location of military bases or scientific developments). The other was ideological—it had to protect against dangerous ideas.

In the republics and regions, the watchful eyes of the censors peered into magazines, newspapers, books, radio and TV programs, stage shows, films, and even private correspondence.

Up above was a completely structured sky: Holovlit was subordinate to the Council of Ministers and the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.

In her monograph, researcher Oksana Fedotova writes that the quantity of forbidden literature in the Soviet Ukraine was approximately equal to half of everything that was published here over the entire 20th century.

In 1974, Holovlit carried out preliminary control of 68,610 printed sheets of books and magazines, newspaper, television and radio content, processed 244,531 meters of film footage, and 10,058 titles of small print publications, reviewed 44,967 copies sent from capitalist countries (9924 of them, works of “anti-Soviet and nationalist content,” were removed), out of 89,203 parcels and packages sent abroad, the censors held 112 shipments. During inspections of 2163 libraries, 614 bookstores and bases, 88 publications were detected and confiscated.

The 1988 list of individuals whose works were forbidden still included, among others, Bahrianyi, Vynnychenko, Kalynets, Stus, Khvylovy, and Chornovil.

Entire editions were removed over decades of checking museum collections, libraries, and bookstores. One or two copies were added to special collections while the rest were destroyed to maintain the state’s supply of scrap paper.

No one calculated the economic losses.

Ideology first.

***

“My father said that the censor lived in him, that he was sitting inside him,” literary scholar Roksana Kharchuk, daughter of Borys Kharchuk, paints a spooky picture of a Soviet writer’s inner life. And against that backdrop, the external censor was unnecessary: the writers knew very well what they needed to write to fit the aesthetics of socialist realism, Roksana is convinced.

It seems there were internal censors working for survival inside many writers, protecting them from an incorrect word, or even its misinterpretation. They were vigilant that no word became a verdict.

“. . . Self-administered censorship became the uppermost regulator of a literary and any other creative process. . .”

From Oksana Fedotova’s monograph

But creative people in the Soviet Union had more than one such line of defense.

Petro Kraliuk, PhD, notes that the first two parts of Kharchuk’s Volyn [Volhynia], which are about the “disgraces” of the times of “masters Poland” (for example, about the forced famine by Józef Piłsudski), were announced a significant achievement in Soviet Ukrainian literature.

The third and fourth parts, where the writer’s internal censor probably caved in, suffered another fate.

This is why on September 18, 1973, the newspaper Literaturna Ukraïna [Literary Ukraine] published a critical review, “Contrary to the Truth of Life.” And there was another three months later: “Borys Kharchuk’s Anti-Historical Exercises.”

This is how Volyn disappeared from libraries.

“After such terrible reviews, which were basically denunciations, everyone pretended that this person had never been a part of literature,” says Roksana, who lived next door to the author of the second, scathing review.

“I didn’t want to, they told me to,” he once spilled when they ran into each other.

And later:

“Roksana, you must be angry with me?”

“How could I reply?” Roksana still marvels today. (Neither her father nor the neighbor is still alive.) “Refuse to shake hands? That’s how everything worked.”

***

I call with caution. A brief pause, and then a hoarse voice, somewhat startled by the call. He happens to be writing an academic article and expected that a call would be about this. I ask carefully if he can suggest anyone. Any of those who crossed out other people’s lines. Maybe he knows.

“You see, I myself was a censor,” surprisingly N. is telling the truth and immediately adds, “But then. . . we signed a non-disclosure statement.”

“Is it still in effect?”

“I don’t know if it is (the hoarse voice laughs). Up until 1992 it was a secret. Even until 1995. So. . .”

(That was 24 years ago, I think to myself. 24!)

Before becoming a censor, he was a metalworker at the Lenkuznia factory. Later he worked in a school and a community college (but he “struggled with the students”). While looking for a new job, he met a censor, a former welder, also from Lenkuznia. He liked N. (“there are sympathies”). This is how he became a censor.

There’s a brief pause and the voice in the receiver is pondering whether to take a risk:

“The only thing I want to say is that censorship was from the bottom upwards. Chief editors of newspapers, magazines and television, directors and editors of publishing houses—practically all of them were censors. They carried out the Party’s task.”

***

Is metalworker-censor-scholar N. telling the truth?

In Ivan Malkovych’s book Bilyi Kamin [White Stone] (1984) the word “God” everywhere became “bird,” and “angel” became “butterfly.” Who did this?

“Not the censor,” says Malkovych, “but the editor.”

There was no drama in this. The author and editor knew each other well and were friends. The former didn’t want to put the latter in jeopardy. A compromise.

But what about earlier? Historian Heorhii Kasianov writes* that Vasyl Stus’s first poetry collection lay on the shelves of the publishing houses for nine years. At first the publishers weren’t satisfied by the author’s ideological and artistic criteria, and later by his civic position.

Besides, there was another link in the inspections: closed (internal) reviews. (Depending on the author, they were either a professional evaluation or another of the censorship’s tentacles.)

For: “Mykola, do you want to make some money? I have a novel here and I need it done fast. It’s a fine novel.” Or “They’ve brought me such shit! Can you ruin it?” literary scholar Anatolii Shpytal recalls bits of editors’ conversations in the publishing houses.

When he himself wrote closed reviews, he had instructions: hide the manuscript in his bag, write at home. So no one would know. Because he had to be objective. But as soon as Anatolii would come from the publishing house to the Institute of Literature, he would get a phone call from the manuscript’s author: “So, Tolya? What’s up? All set?”

There were no secrets.

It is known* that three reviewers in different years, generally recognizing Vasyl Stus’s literary talents, pointed to the significant ideological-thematic and artistic errors in his poems from the collection Kruhovert [Vortex]. None of them is still alive; no one will tell you if they were really thinking what they wrote. But Stus’s poems then went to samizdat (dissident underground press in the USSR — R.).

What else could be done?

“Resort to allegory, write “for the drawer,” or do something defiant,” lists the options literary scholar Volodymyr Morenets.

Defiant, for example, like Lina Kostenko, who refused to publish “corrected” poems.

And since she refused, she was silent from 1961 on. Only in 1977 did her collection Nad berehamy vichnoyi riky [Over the Banks of the Eternal River] appear. Still, an entire stanza was missing from one of its poems:

I’m sick of the covens of fictions

and this confiscation of souls to an accordion.

In the twentieth century, sometimes I long

to hole up in a cave and nurse the fire.

“For it’s a Russian accordion, of course. It’s an allusion to russification,” says Morenets. “Giving this book as a gift, Kostenko always wrote in this stanza. In my copy she added, ‘I give you this crippled book. . .’” So she came to terms with it, but she never agreed.

Still, it was possible to make a play for the censors, to attempt evading censorship somehow. To submit a little and dodge a little, like Dmytro Horbachov, a disobedient employee of the Kyiv Art Museum, who in the 1960s arranged secret tours of the special collections where the paintings of Ukrainian avant-gardists were locked up. He later wrote many essays gradually revealing to Ukraine its own avant-garde.

“I remember how I wrote for the journal Vsesvit [Universe] about the 1920s, wrote that art in Ukraine then was at the highest level! At that time this wasn’t a very desirable topic. And Korotych, the editor, was forced to reckon with this. I’m looking at the proofs and after every one of my phrases, like a mantra, was ‘our great party.’ It was grotesque! Korotych said they wouldn’t approve it without this stuff and that readers are smart and would ignore it and retain the important information.

“For two nights I thought about whether or not to publish the article.

“Why? I didn’t want to be an opportunist or a sycophant. I didn’t want to factor in the censors. I wrote about the avant-gardists and titled my articles ‘Born of the Revolution,’ but in my soul I knew they were ‘born of the national revolution.’ Yet the main thing was that people simply learned about these world-class artists.

“We once published an album with images of the saints at the Dnipro publishing house. The director wanted the book to come out, but they all had halos—obviously they were saints. ‘Can’t we just scratch them off?’ he asked.

“I got crafty and added the line: ‘Look at that Gothic ornamentation in the margins!’ And the censor paid no attention to those halos. We were told not to publish the book, but to send it out for review. And guess what? Ten positive reviews! Not a single scholar wanted to get his hands dirty. Everyone wrote that it was outstanding!”

***

“Yeah, yeah,” I hear the hoarse voice of the metalworker-censor-scholar N. in the receiver. “Let me tell you again: we were mainly protecting state secrets. None of that ever even reached us. They brought us proofs, but they, they were already purged. Don’t think that it was us (he laughs) who were so terrible. I don’t remember cutting anything between 1983 and 1995 when I was a censor. It was all done at the hand of the publishers or the directors of the publishing houses and magazines. We were all doing the same job. If someone didn’t know something out of naivete, then the censor would make ever so slight corrections. Just to point it out! We didn’t cut. We’d simply call in the editors and tell them that we couldn’t, he-he, ‘accept’ this. We cut nothing. . . (he laughs).”

Being more literate than the censors, the editors posed an even bigger threat to writers, for they noticed what the former would not. The editors watched out most cautiously for texts to evoke no series of so-called uncontrollable associations (. . .) Since the 1940s, any text edited in this manner practically no longer caused any censorship claims, except for occasional disclosure of “military secrets.”

From Oksana Fedotova’s monograph

N. can only recall two forbidden topics: repressions and the Holodomor. Oh, and you couldn’t write anything good about the Nazis.

“Aha. You want to know about the code? Andrukhovych wrote about it in his story, right? Two letters and numbers? It was a stamp! A round one. It meant that everything was fine and it could be printed. If it turned out in Moscow, that it wasn’t fine, then they used it to determine which of the censors let it through.”

N. is now retired and lives in Kyiv. He turns down my request to meet like it’s an invitation to the end of the world.

“No no no. I’m a busy person. But there’s K. He’s never hidden that he worked for Holovlit. He loved going to Moscow. Maybe so they’d give him an apartment. But I don’t want to talk. No no no.”

***

K. is looking at me with disappointment. He’s tall, sedate, and wearing a perfectly tailored suit. He has perfectly combed gray hair. He looks like a manager of some important outfit. Which is exactly what he is.

K. really doesn’t hide that he was a censor for Holovlit, but he won’t let me name him in my story.

“So it’s not a dissertation that you’re writing? Eh, then nothing will come of it. Only a scholar can write about this, otherwise people won’t understand,” it seems like K.’s assistant didn’t really check to see who requested this meeting, and now K. is truly sorry that I’m not a scholar.

But after some brief cajoling, for some reason he feels sorry for me. He melts into the black leather chair and gives me half an hour for my questions. As long as we’re talking about general things, he willingly gives detailed answers.

That the censors called themselves “editors.” That they had an ordinary office with ordinary desks (“don’t mythologize it!”), one, two, three, or at most four ordinary people. Surrounded by manuscripts, proofs, and drafts. Read, read, read, stamp “approved for printing” (with letters and numbers), register it in the journal. Lift and stamp. Read, read, read. Morning, lunch, evening.

A lot.

Stamp.

As for his own experience, he cuts me off monosyllabically—don’t ask.

Stamp.

For example, from K.’s official biography, it is known that two years after he graduated from the university (what he did those two years, he doesn’t say) he got a job with Holovlit. Could he, a young man, really know where he was headed and what he would be doing?

“Working with texts,” he says without batting an eye.

“Did you understand just what you would have to do?”

“No, because Holovlit’s functions were multifaceted.”

“But what did you do?”

“Various things. I worked in different departments.”

There we go around in circles. From the general to the concealed.

“Were your relatives screened for reliability when you applied for this job?”

“You shouldn’t think like that. It was an ordinary organization that executed specific functions.”

I return to this question in a little while. Something has changed in K. It’s like he’s remembering how he was in the 1980s, like he’s becoming his 1980s self: a boy looking for work. He looks hard and he finds it.

“Let’s say, it wasn’t the job of my calling. But one has to fulfill certain duties at work. Right? And to make money to provide for the family. Right?”

“Was it interesting?”

“Yes and no. On the one hand, one had the opportunity to receive an enormous amount of information (again all the “I”s disappear from the conversation, again it is “one,” someone with a stamp). On the other hand, it was routine, because every month one had to churn out a whole lot of pages.”

What did K. cut from the books, newspapers, magazines? What was he looking for? He doesn’t say. Just like N., some things from the list of state secrets. Nothing ideological. He only recalls how he counted the number of religious images so there wouldn’t be too many. But otherwise, it’s like there was nothing and no one to break through anymore.

“Look, everyone blamed the censors: ‘The censors didn’t approve.’ But the censor was only the final, control link!”

“[At the end of the 1980s – Author.] censorship organs reported to the appropriate Party committees only on serious issues (without interfering with the actual content). (. . .) During 1987, there were almost ten times fewer issues with the content than in 1984.”

From Oksana Fedotova’s monograph

Becoming this control link (usually these were people with higher educations) required special preparation: the “School of the Young Editor.” There K. studied documents, and later he “watched the practice.”

They issued him the stamp immediately. But for a while K.’s work was checked by a senior colleague with a seasoned stamp. Representatives from the Academy of Sciences, the Central Committee, and even writers delivered lectures to the Holovlit staff—you could learn a lot.

“Writers? So you controlled them, and they delivered lectures to you?”

“You don’t understand. It was a system. Everything was intertwined. Pardon me, but who were the heads of publishing houses in that period? As a rule, they were people related to the ideological department of the Central Committee, who had in their own time worked there as instructors and secretaries. The editors and censors drank tea and coffee at the same tables, conversed. There are people everywhere. . .”

“You asked if I had relatives in sensitive files,” K. suddenly breaks off, and sinks deep into his black chair as if he’s drowning. He crosses his arms and stomps his feet. “I’m from Western Ukraine. My parents were connected to a different movement.” The pauses between sentences grow longer and more measured. There’s a risk, it seems, his sentences will end here once and for all. “You had to live. . . develop. . . think about the future. I came there after being in intelligence (here’s where K. spent the two years between university and Holovlit!)—I served in the Main Intelligence Directorate of the Soviet Army. Any system selected the intelligent. As for the ‘purity of the ranks,’ that was a different matter.”

“What did your parents say when you became a censor?”

“My parents? They were smart people. And I’m not ashamed of the job I had. I always write about it openly.”

“But it seems like it’s an unpleasant topic for you.”

“Well, how might a person feel when the whole state was a system? Everything was re-gu-la-ted: what to do and how. There was control everywhere.”

“I don’t know how. I didn’t live in it.”

“Well, I did and I don’t know either. We didn’t think about it. We existed. At that time we belonged to that system. . . And you know, I’m proud that there are films about Chornobyl that Moscow didn’t want us to pass through, yet they came out. (One of the films featured eyewitness testimonies about the disaster that were inconvenient for the government. — Author.)

— ? . .

“I was responsible for that. My censor stamp is on it. My stamp. The stamp they know you by in this world.”

A stamp with a code.

“Which is why I don’t want to talk. Because people won’t understand. They won’t understand that such a system should have never existed!”

This was K.’s first conversation about his former job since he had left it. And maybe the last.

***

A memo from October 12, 1989: “In connection with the recent increase in appeals to our organs from various categories of citizens. . . Holovlit Ukraine considers it expedient:

to return works by the following authors from special collections and transfer them to general library collections: Polonska-Vasylenko, Ohienko, Khrystiuk, Shumsky, Vynnychenko, Khvylovy, Yefremov, Rudenko, Stus, Sverstiuk.

(. . .) to retain in special collections publications by the following: Bahrianyi, Ohloblin, Sheveliov, Shtepa, Kalynets, Moroz, Svitlychny, Chornovil.”

On January 17, 1990, Holovlit UkrSSR’s final directive was issued: “All previously issued lists and orders. . . on this matter should be considered null and void.”

* from the book Nezgodni. Ukraïnska intelihentsiia v rusi oporu 1960 – 80-kh rokiv [Dissenters: The Ukrainian Intelligentsia in the Resistance Movement of the 1960–1980s].

Translated by Ali Kinsella.

[This publication was created with support of the Royal Norwegian Embassy in Ukraine. The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Norwegian government.]

Have read to the end! What's next?

Next is a small request.

Building media in Ukraine is not an easy task. It requires special experience, knowledge and special resources. Literary reportage is also one of the most expensive genres of journalism. That's why we need your support.

We have no investors or "friendly politicians" - we’ve always been independent. The only dependence we would like to have is dependence on educated and caring readers. We invite you to support us on Patreon, so we could create more valuable things with your help.

Reports119

More