(Un)Laid to Rest

“Oh my God!” Standing startled on a high earth fill near the highway leading to Novoyavorivsk, Lyubomyr Horbach was staring at the ground under his feet, sown with human bones: broken, mixed with soil, grass, and some personal items. Ten freshly dug six-foot holes.

The eternal peace of the soldiers, who found here their final resting place in the years of World War I, was disturbed this summer. Looking at the things the “black diggers” were not tempted by, it was clear: this was a mass burial ground for Russian and Austro-Hungarian soldiers made in 1914. Horbach counted 15 bodies. It is not an easy task to collect them. While looting, grave robbers scattered the bones all over the place.

Activists of the Memory War Victims Search Society see such things almost daily.

Open Graves

“If we fail to find the remains today, some digger will find them tomorrow. We will still have to go back to this burial site in a year or two, but there will be nothing left to exhume,” says Horbach, who is the Head of the Society.

He classifies diggers into three categories. The first two are fan collectors and antique dealers. These have one thing in common: when they come across remains, they stop digging and call the Memory Society. However, human bones will not stop diggers in the third category.

It is difficult to recognise such people by their looks. You see a man in the woods carrying a metal detector, dressed in dirty clothes, soil on his shovel. This is not a crime. You need evidence and proof.

“Guys, in case you come across any remains, please try not to destroy them. Call me at once. Would you? Here is my card,” Horbach usually says to such people.

“Oh, no, we are reasonable guys; we would not do anything like that. We will give you a call,” they reply in most cases.

It is because of the black diggers that volunteers search for soldiers’ burials to find the remains ahead of the marauders and grant them a Christian burial.

“Sometimes, people would find some bones, give me a call, and I know that I would not be able to make it there tomorrow or the day after. Then, I would ask them: pick up everything the metal detector responds to. You can give it to me later, but bury the bones or otherwise cover the site up somehow,” the man says.

And people do listen and keep the things safe. If they are able to find the relatives of the deceased, the searchers will give personal belongings to their families.

Only Their Things Speak for Them Now

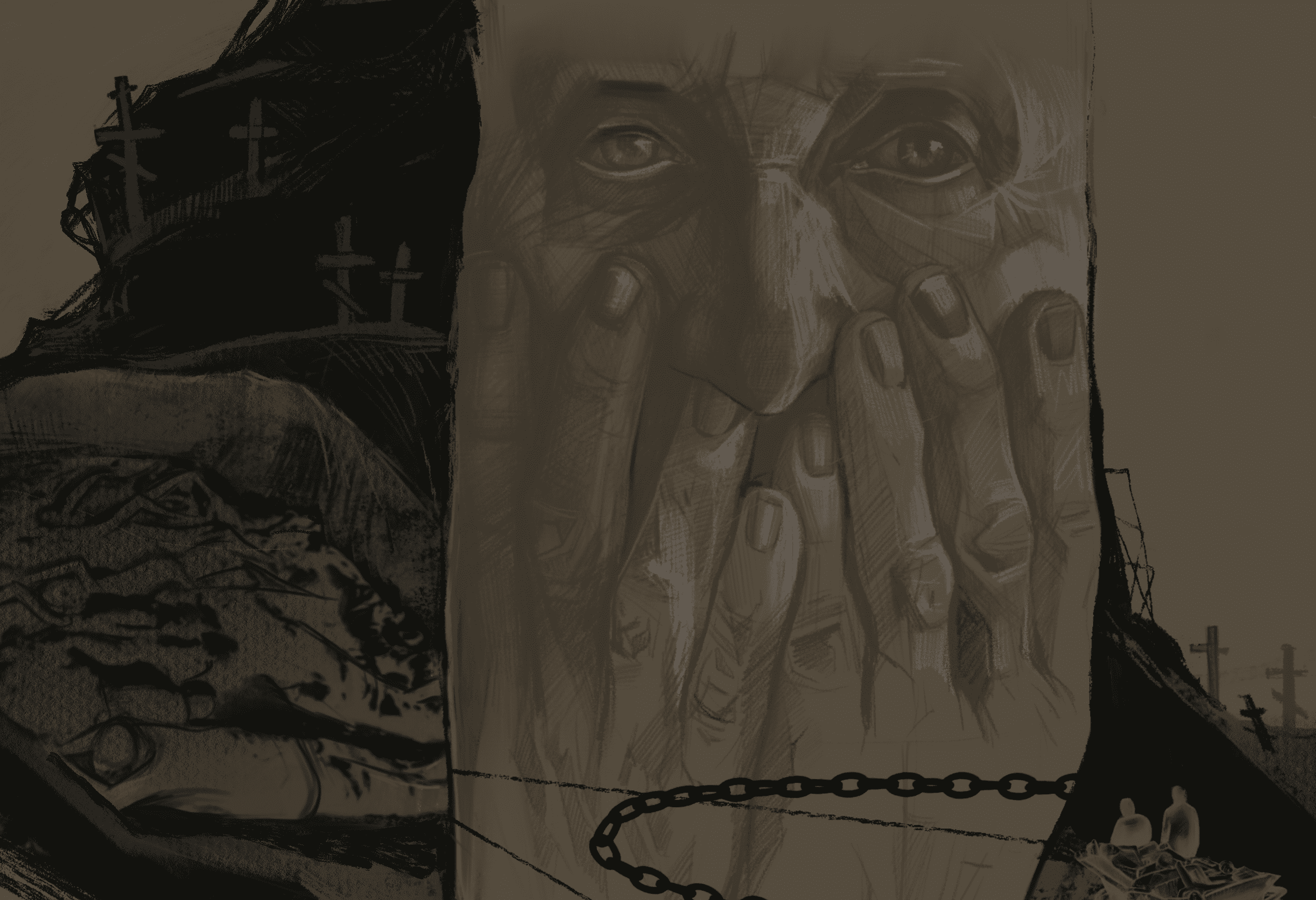

The brush makes a sandpapery sound as the crumbs of soil fly away with each stroke. After the years of experience, the searchers perform this movement automatically. The outlines become visible in an hour or two—brown-orange bones, rusty shell casings, helmets filled with earth.

Based on the positions of the remains, one can understand what happened in the last minute of a person’s life. Most of the found soldiers were buried worse than animals. After his pet passes, a good master does not throw the body by the roadside. Yet this does happen to soldiers.

Face to the ground, the right leg and femur are torn off. Apparently, before his death, the soldier was running; then, something exploded to his right and ripped his limb off. The soldier fell flat into the pit. By the looks of his remains, it’s clear that no one moved his body, and he was simply covered with a thin layer of earth.

The brush makes another sandpapery sound, and we can see a shining baptismal cross.

Almost every soldier has icons, medallions, crosses to be found, no matter where they served: German, Austro-Hungarian, Polish, Soviet or rebel armies. The searchers also come across folding knives, toothbrushes, spoons, forks, remains of military leather equipment, shells or helmets. Wedding rings are rarer.

“We make a point never to touch personal or spiritual possessions, something a mother or a wife might have given them before they went to war. Despite any historical value, those things are reburied with the remains,” Horbach emphasizes.

Sometimes, a soldier was already reburied, but his possessions were left out. Searchers keep them, hoping to give them to the family. When they fail to do so, they will drill a hole and bury the things in the owner’s new grave.

Horbach knows almost all the names of the found soldiers by heart.

“How do you do it?” I ask him, astonished.

“There are not too many of them. Of the one and a half thousand remains we have found, we have confirmed less than fifty identities. They are easy to remember.”

There are even fewer families found.

Dad Is Nearby

In 2005, in the village of Leshniv in Brodivskyi District, searchers found traces of explosions in the forest. The entire area was covered with craters of considerable size. Some battles are known to have taken place here in 1941. One surviving soldier described them in his memoirs. A memorial sign to honour the fallen was erected near the craters in Soviet times.

“We were wondering whether they collected the remains of the soldiers when they were constructing this monument,” Horbach recalls.

So they went to the forest. Exploring shafts revealed human bones. They discovered the remains of 60 Soviet soldiers.

“They left all the soldiers on the battlefield. They put up the sign and left the dead in the ground,” the man says, surprised.

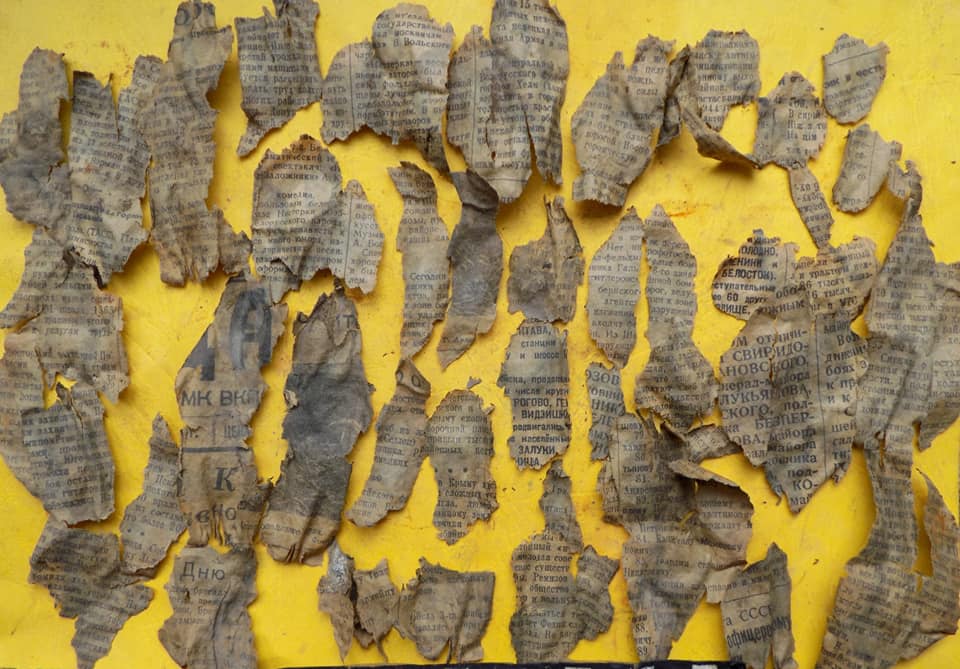

There was someone special among them. The soldier had a badge with personal information: Pavlo Avdeyev. Place of birth: Yarki village, Voronezh Region, Russia.

In 1939, he came to Western Ukraine along with other units of the Red Army. He served in the town of Stryi in Lviv Region, and married a Ukrainian girl. When the war started, he was sent to the front line with his unit. His wife was likely evacuated, first to Kyiv and then somewhere far into Russia. After the war, she returned to Ukraine and settled in Zolochiv. Their son, following in the footsteps of his father, became a military man.

The search for relatives started in his native village. The activists called the village council. It turned out that, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, Avdeyev’s wife and son left Ukraine for Moldova. But his sister still lived in Yarki.

“She is over ninety years old, but do not worry; we will tell her the news,” Horbach heard on the phone from the village council staff. Then, the case was brought to a halt. A year later, the searcher received a call. The number was unusual, likely foreign.

“Hello. Are you the one who found Pavlo Avdeyev?” someone said hesitantly on the other side.

“Yes, I am,” said Horbach.

“I am his son!”

Avdeyev’s sister had received the information after all and passed it on to her relatives. The son wanted to come and see where his father had been found. He even brought his own son. The searcher took them to Leshniv.

As they walked through the woods to the craters where they had found the soldier, Avdeyev Jr. was noticeably worried.

“We found him right here. There were five of them in this pit. Your father was the only one to have a capsule with his name—a small metal capsule with personal data, like a cylinder, the size of a match. The rest of the soldiers remained unknown,” the searcher explained.

The soldier’s son was listening in silence. Then, he took some soil from the crater where his father had been found and asked to be shown the place of reburial.

“For the past 20 years, Russian propaganda has been constantly harping that, in Western Ukraine, the remains of the Red Army soldiers are thrown out of their graves, and their bones are mixed with asphalt,” Horbach recalls their conversation.

The men went to Brody to see the World War II memorial. It has been tidied up. Behind the old Soviet monument, there is a new granite one. It bears the names of the fallen, including Pavlo Avdeyev.

His son was shocked. His mother and he had been searching for their husband and father all their lives. They had written to the USSR Ministry of Defence. They’d received the same answer as many other relatives at the time: “Missing in action in July 1941,” either near Kyiv or near Leningrad. And all this time, he’d been just 30 km from their home.

Horbach has his own searching story.

Over a decade ago, he became a searcher in part because of it.

A Birch in the Nobleman’s Garden

“I have been interested in history ever since I was a kid. I have probably read all the books in the school and district libraries about wars, the age of principalities, the Cossacks,” says Horbach.

Yet, he did not pursue a degree in history. His family moved from Novyi Myliatyn to Lviv when he was just a boy. His parents worked at the Lviv Bus Factory, so Horbach started training as a maintenance technician at the factory’s vocational college. Yet, he did not become a maintenance technician either.

In 1989, the country faced turmoil.

“It is crazy out here,” he heard his classmate saying once. “We will chase the Russkies out. We have already hoisted the yellow-and-blue colours. Come to the Gunpowder Tower; the patriots will gather there.”

The rally was brought on by the events of 1 October 1989, when special-purpose squads of the Lviv militia brutally beat protesters in the Kopernika Street after the celebration of City Day, when 70 state flags of the USSR and the Ukrainian SSR were torn down.

Horbach went to the meeting and started taking active part in protest meetings across the country after that. They went to the east and moved around the villages handing out leaflets saying “Away with the Soviet Union.” He had to learn more about history reading books, but they were few. Some were brought from the diaspora. There was a line-up of 40 people to read one book on the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UIA). They had to read it overnight to give it to someone else first thing in the morning.

“Then, I started asking my grandmother whether grandpa had anything to do with the UIA, and she started spilling the truth little by little,” Horbach recalls.

Maria told her children that her husband had been taken away by the Germans. In fact, Antin Horbach was killed in a fight with the NKVD (the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs, the interior ministry of the Soviet Union in 1917-1930, tasked with conducting regular police work and overseeing the country’s prisons and labor camps — R.). In the photo, he is depicted in military uniform, holding a carbine and wearing a “mazepynka” (a traditional Ukrainian military hat — R.), on his head. Young and handsome. His grandson wanted to find his grave. He only knew that, after his death, his grandfather was taken to the Lopatyn prison for identification, but, at night, the partisans stole his body and gave him a Christian burial. The wife was told that Antin was buried in a nobleman’s garden, with a birch tree as his headstone. They would not tell the exact location of the nobleman’s garden, because the NKVD would have taken away the family as well.

Horbach looked for the nobleman’s garden for a long time to no avail. Instead, he became the founder of the Memory War Victims Search Society.

“I would really like my grandpa to be found. It’s disheartening to think that someone has already dug his grave and thrown away his bones.”

(Un)Laid to Rest

Over 13 years, the searchers have found more than one and a half thousand mortal remains. Some were given to the families. Most were reburied. Some are still between worlds as there was not enough space for them in the cemeteries.

In Ivano-Frankove, on the high hill in the very centre of the town, Pope John Paul II is smiling. “Have no fear,” he calls from his pedestal. Behind the statue, there is a snow-white Polish church dating back to the 17th century, the oldest local monument.

The remains of Princess Konstancja Czartoryska, the mother of the last king of Poland, are buried in the vaults underneath the temple. In recent years, several dozen small black coffins have been brought here. Cemeteries did not have enough space to bury the remains of these soldiers.

Local authorities faced the challenge back in 2005, during the first exhumation. Remains of the Red Army soldiers killed in 1941 were found in Khmeleva village in Zolochiv district. There were 14 bodies and not one intact skeleton; black diggers had done their job.

The searchers wanted to rebury the remains in the Khmeleva village cemetery.

“We have no space to bury our own people, and here you are trying to bury some strangers,” representatives of the village council told the Memory Society.

The soldiers were buried in Brody, in the cemetery at the town’s exit.

There is mostly no place to rebury the Ukrainian soldiers and those who served in the Red Army. The situation is much easier for the Germans, Poles, and soldiers who were killed in World War I.

The German War Graves Commission takes care of German soldiers killed in World War II. They do it in all countries where German soldiers were involved in hostilities. When searchers find Germans, they contact the Commission, and it gives permission for the search and exhumation. The Germans are reburied in Potelychi village. There are more than 15,000 of them so far.

The Germans kept thorough records of their soldiers. Each soldier had a tag or an identification disk on his neck. Good luck or bad, they had to have an identification tag. The same applied to the soldiers in the 14th SS-Volunteer Division “Galicia,” i.e. the Ukrainians who served in the German army. The tags had the soldiers’ personal numbers and units, e.g. 14. Gal SS-Frw. Div.—that is, 14. SS-Freiwilligen Division “Galizien.” German archives still keep regimental books, which contain soldiers’ data next to their numbers.

The Polish army also had identification tags with full information. But the soldiers rarely wore them. The remains of Polish soldiers are reburied in the old city cemetery in Mostyska.

The soldiers who served in the 14th SS-Volunteer Division “Galicia” are reburied between the villages of Chervone and Yasenivtsi. There is a collective cemetery founded in 1995 by the remaining soldiers who served in the division so that their brothers-in-arms would be buried with honour.

The searchers rarely find the soldiers killed in World War I. The Sich Riflemen (a military unit of the Army of the Ukrainian People’s Republic operating from 1917 to 1919 — R.) buried their fallen brothers on their own after the battles, as did the Austro-Hungarians. In the 1930s, Austria, Germany and Hungary allocated funds to the cemeteries for the Polish state, which, at that time, was ruling over Galicia. The sites of mass graves were investigated, excavations were made, and the fallen were reburied. For this purpose, they bought land plots near cemeteries and churches.

The Memory Society used to rebury the Red Army soldiers either in Brody or in Rava-Ruska.

“The year before last, we buried another 25 soldiers, laid them to rest somewhere between the coffins. This year, we planned to do that again, but there was no space, unless we wanted to make a third tier,” Horbach recalls.

Polish Provocations

April 2017. Several Polish men, about 40 years of age, come to the village of Hruszowice not far from Przemyśl. Wearing hard hats, gloves and protective goggles, they head to the cemetery with an angle grinder. Their target is the two-meter-long arch-shaped monument with a cross at the centre and a trident at the top.

Bang! The metal ladder hits the monument loudly.

A big guy wearing a chequered shirt is the first to climb up to the top. Next climbes a man wearing a t-shirt with a crossed-out portrait of Stepan Bandera. They turn on the angle grinder and proudly cut off the trident for the camera. Then, one by one, they aggressively crash the stones of the monument. Their friends are gleefully taking photos and videos of this on their phones.

Prior to that, the remains of Polish soldiers were actively searched for and reburied in Ukraine.

“Your monuments are destroyed in our country, and you are reburying our soldiers with honour—why?” Horbach recalls how the delegation from Warsaw was surprised a few years ago. There was still a chance to handle the situation, he noted to Polish politicians. But the trident cut in Hruszowice was the last straw. The 2017 permits for the exhumation of Polish soldiers were ready, but Horbach was told to stop his activities.

Earlier, the searchers were notified that a Polish officer was buried in one of the villages in Yavoriv district. At the time of his death, he was accompanied by a German soldier who asked the villagers to bury his brother-in-arms. People kept the promise and buried the soldier by the road. They looked after the grave until the Soviet regime came in 1941. The burial ground was destroyed, and the field was transferred to private property and ploughed with the grave.

Later, this piece of land became the property of a local resident. Searchers started their research and found out that the body was located right below the barn where the old man was keeping his hay.

Horbach went to the old-timers to ask if anyone knew anything about the soldier.

“His name was Stefan, and he was from Yarosław, but we cannot remember the last name,” they told him. The searcher left his card. Two weeks later, he received a call.

“They found another man who buried that body. He says the Pole’s family name is Łevyćkyj.”

Knowing the family name, the given name and the place of birth, it would be possible to rebury the soldier and search for his relatives, but the events in Hruszowice cancelled the plans. Stefan Łevyćkyj from Yarosław is still buried under that barn and will likely stay there for years to come.

“Unfortunately, historical truth is interfering with political struggles. It seems like the only ones caring for it are us and our children,” says Horbach.

Bureaucracy

Stacks of papers and months of waiting. Ukrainian legislation is the biggest obstacle to the activities of the Memory Society, Horbach says. The Ministry of Culture’s permit to conduct search operations is valid through the end of each year. When issued on December 1, it will be valid for exactly 30 days. This was the case with the search in Busk. They had no time to excavate due to the snow. This year, they were given permission in May.

As the Head of the Society, Horbach has been reporting about its activities to the Ministry of Culture for the past 10 years. He describes his works and discoveries. He says that this is how the ministry filters out organisations using the search for the remains as cover-up for profiteering.

“If they report that they received permits for 10 settlements and did not find anything, it is clear what they were looking for. And we have 10 settlements and find 10-15 mortal remains in each of them. Our reports have been like that for the past 10 years. The Ministry can see that we are not some fraudsters. So, give me that permit sooner; do not wait until the summer,” the man says indignantly.

Sometimes, a person would accidentally come across remains and call the searchers. But exhumation permits are issued subject to permits for searches, so they are forced to wait a few months, though everything has already been found.

“Are you not offended by such bureaucracy?” I ask him.

“I get frustrated, I might yell—and then, I start writing applications and asking again. No one will do that but us. They will mistreat the graves and move on,” he replies.

Over thirteen years of work, the searchers found a lot of associations with the word “mistreatment.”

Memorials

“Hello! Good afternoon. My friends advised me to contact you. There is a Red Army soldier, by the name of Kryzhanivsky, in my garden. Is there any chance for you to take him away to a cemetery? I really don’t need him here,” the man on the other end says uncertainly. Horbach promises to come.

A middle-aged man is leading the way in the village of Hostyntseve in Mostyska district.

“It is not far from here,” he says and soon shows the offending plot to the searchers.

There is a cross between the trees in the middle of the garden. The rusty brass displays the family name, the given name and the date of death.

The searchers remove the cross and start digging. They find bones, yet half of the skeleton is missing. There are some artificial flowers mixed with the soil—the remains of a wreath. It turns out that, in Soviet times, village authorities were widening the road and accidentally opened up this soldier’s grave.

“They collected what they could see and quickly buried that man in the nearest garden. It is obvious they were in a hurry. And then, they reported it to the regional committee of the party, their bosses arrived, threw a wreath, had a shot and left. The rest of the remains are still lying separate from Kryzhanivsky,” says Horbach.

The searcher believes the Soviet Union’s attitude toward its own and other countries’ soldiers was equally indifferent. That is his main conclusion after 13 years of work. The regime deliberately destroyed the burials of its enemies; they used to pull down crosses with construction machinery, level cemeteries to the ground and build maintenance buildings on top of them.

The fate befalling our own people was not much better. In Zozuli village in Zolochiv district, the Soviet soldiers who had been killed in battles and died in hospitals nearby were buried on the village outskirts back in 1944. And, in the 1980s, local authorities took the soil mixed with bones and paved the road, Horbach says.

Searchers found two remaining burial sites located by the road, an officer and a private. Both were in their coffins, because their remains were intact. One was cut on the side of the legs by a bulldozer making an earthen mound for the road. The other was crushed by a compactor. The village council kept letters from the locals saying, “Those are Soviet soldiers there. How can you do this? Rebury them first and then pave the road.” The archives of the Ministry of Defence of the Russian Federation indicate that these soldiers were reburied at a military memorial in the city of Zolochiv.

“That road is still there. It cannot be taken down since the road fill is three meters deep. We reburied the discovered remains in Brody and marked the place where we found them with a granite cross. Its epitaph says in gold letters that the cross is commemorating the soldiers of the Red Army whose burial was destroyed by the Soviet regime,” Horbach says. “The Ministry of Defence of the USSR was informed and had layouts of many soldiers’ burials, but no one ever reburied them. They issued formal letters saying the soldier was moved to a war memorial. Perhaps the reason is the innumerable losses.”

No one thought at the time that, 80 years later, anyone would start looking for these remains.

Christians and Heathens

The new war brought new work. The People’s Memory Association started searching and exhuming people killed in Donbas in 2014, after the first fights.

“Once Ukraine gets back its control over Donetsk and Luhansk, should we look for the remains of those who fought on the other side of the front?” I ask him.

Horbach falls into a muse.

“There is a difference between forcibly “conscripted” soldiers and terrorist leaders. Some people got draft notices and were told to come to the recruiting station the following day. Not many, especially among the young, would have the willpower to refuse serving them. But the leaders are terrorists; there is nothing to look for and rebury. What is the main reason for us to rebury the remains, you might ask? Because we are Christians, and this is our tradition. And they acted as heathens. There should be no crosses and honours on their graves. They served the devil.”

The searchers have their own story about terrorists. Back in the days of Viktor Yanukovych’s presidency, Yevhen Zhylin, later the head of Oplot (a fight club from Kharkiv whose members attacked the protesters and press during the Revolution of Dignity in 2014 — R.), had a crusade against the Memory Society in Lviv. He called it a “pro-fascist organization,” wrote to the Ministry of Justice, and sued it in courts. He pestered them for a year and then piped down.

True to Oath

The searchers have never been paid for their work. In 2014, the region started funding them. The annual budget covers just the transportation, food, tools and everything required for reburial. There is no funding for salaries; all volunteers have regular everyday jobs. Excavations are carried out on weekends.

“Some people go fishing, some hunt wild boars in the forest, some have barbecues. While we are looking for the fallen, driven by a moral obligation. Because looters will come tomorrow and rob the dead soldiers,” Horbach says.

There are no horrors or mysticism in the life of the searcher, but there are plenty of reasons to empathize. Once they found remains of Jewish people in a village. People were lying on their backs in a row, surrounded by piles of shell casings. Obviously, this was how the poor souls were waiting for the execution. One woman was holding a small baby in her arms, covering its eyes with the palm of her hand.

Perhaps because of the emotional difficulty of the work, new members of the Society rarely choose the direction of reburial. One in 20 will. The rest are engaged in historical and military reenactments or making movies.

Horbach never regretted moving further. In 2014, after the events in Ilovaysk, he received a message saved to this day on his phone. It was sent from an unknown number, just one sentence:

“Thank you for your work; it is the reason I’m still serving in the ATO (Anti-Terrorist Operation, the Ukrainian government’s operation in the War in Donbass, 2014–2018 — R.) and true to my oath.”

[This publication was created with support of the Royal Norwegian Embassy in Ukraine. The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Norwegian government.]

Have read to the end! What's next?

Next is a small request.

Building media in Ukraine is not an easy task. It requires special experience, knowledge and special resources. Literary reportage is also one of the most expensive genres of journalism. That's why we need your support.

We have no investors or "friendly politicians" - we’ve always been independent. The only dependence we would like to have is dependence on educated and caring readers. We invite you to support us on Patreon, so we could create more valuable things with your help.

Reports119

More