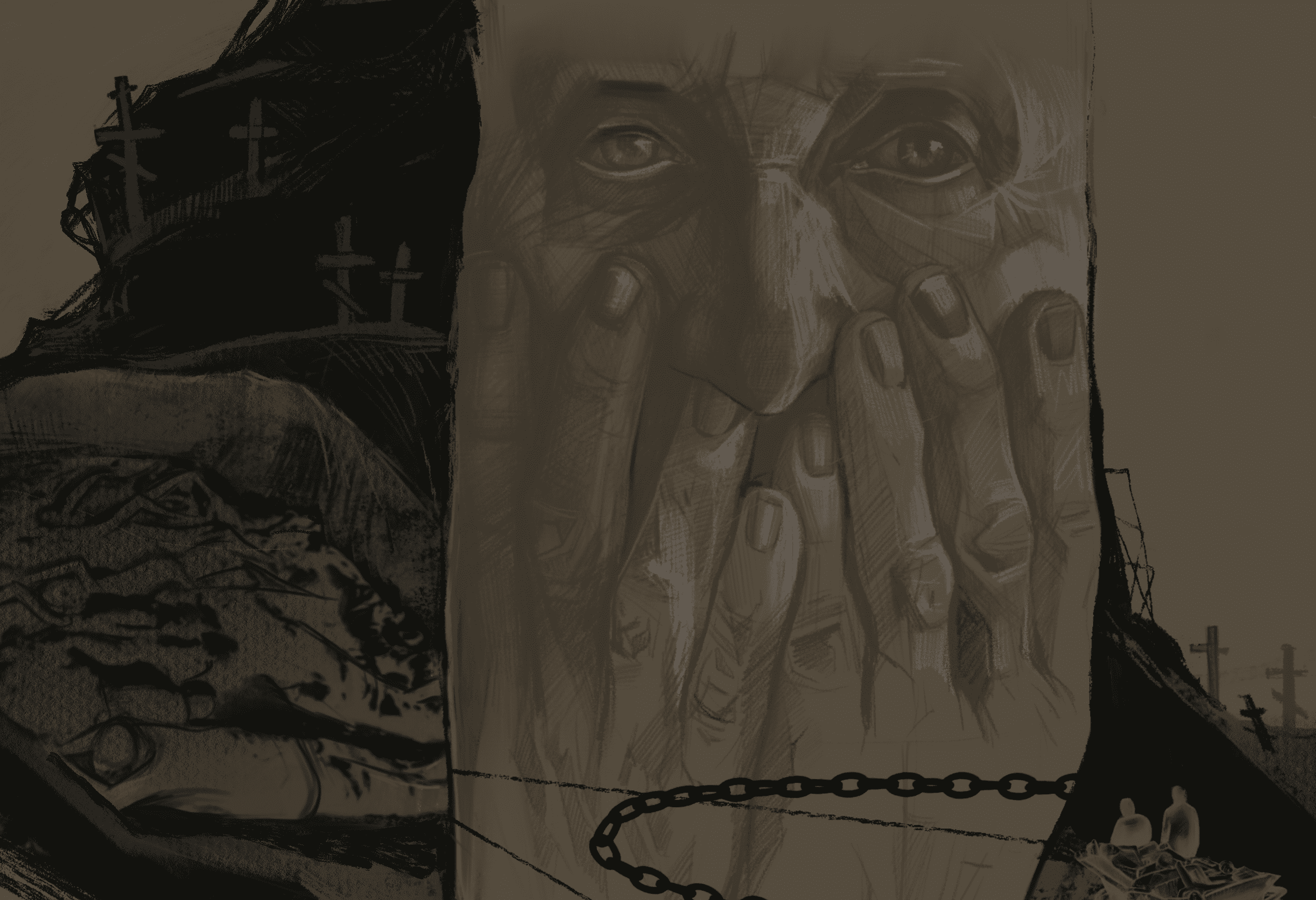

Lucky Man

Two years ago, Ivan Masliuk was traveling around Europe with his friends. It was more than just a trip—this guy with cerebral palsy covered thousands of kilometers by bike in order to see the ocean. After he fulfilled his dream, new ones appeared.

Today Ivan is a volunteer helping people with disabilities conquer mountains. After their adventure together, he and his friends established the organization On 3 Wheels—he felt it was something he had to do. Once he felt the freedom of making his own decisions and managing his own life, he decided to give this freedom to others. Now he shares his experience with others with disabilities.

A car is parked at the entrance to the Malevich nightclub. A girl with crutches is helped by two people out of the car. Her name is Olenka. Ostap shouts at her from far away and then approaches her slowly, leaning on the man walking at his side. She is glad to see him, but it is difficult for her to express her emotions: because of her disability, Olenka cannot speak.

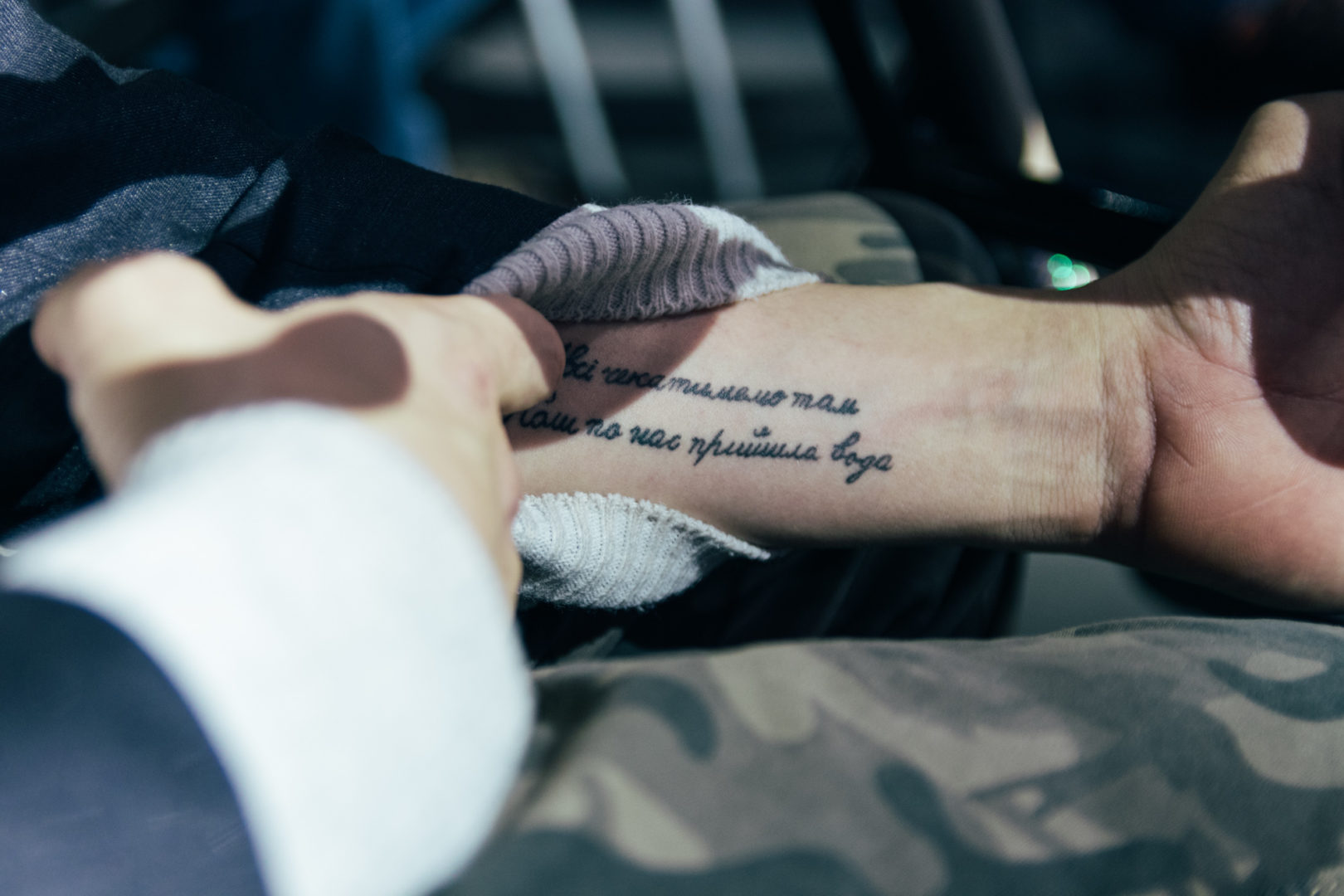

Even if Olenka cannot speak, she can still listen. At the accessible party in Malevich, she listens to Ivan. He has a tattoo, likes parties, discos, and get-togethers in dormitories, and advocates for the legalization of marijuana. But Ivan will make no mention of this—he will only talk about his trip from Lviv to Lisbon on a three-wheeled handcycle to see the ocean. Even though he has cerebral palsy.

“It’s the one who has mental barriers that is truly limited, not the one who faces physical barriers,” explains Ivan.

“Can you hear him talking about mental barriers?” a man at a table near the stage repeats these words to a disabled boy sitting next to him. Perhaps it’s his son.

The boy nods. The audience applauds Ivan.

І. To the Ocean on Three Wheels

During his presentation, Ivan Masliuk is at ease because he speaks in public two or three times a month. He is often invited as a motivational speaker—how hard could it be to tell about his trip to the ocean? However, his first meeting with people with mental illness in the Polish city of Tarnów remains etched in his memory.

“It was one of the most terrible days in my life. I could not speak Polish at all. The guys translated it, but people did not take it well. Speaking into the abyss was incredibly difficult.”

For a hundred days, Ivan and his then small On 3 Wheels team covered 5000 kilometers across twelve European countries to reach the ocean. This, however, was just the beginning of the story.

Have You Gone Mad?

The story starts in the village of Berezivka, near Lviv. The year Ivan was finishing 11th grade, he played football and exercised on workout bars in front of the school to keep fit. Lviv was as far as he could go without supervision.

The 19-year-old boy helped his parents around the house. He never refused to do anything but most of all he liked shelling beans—this is the best chore for an introvert. In the evening, Ivan usually watched videos, read books, or listened to music. On the weekends, he used to go to the disco. Not much has changed.

At the summer recreation center in Berezivka, people dance, fight, kiss, and drink. They come to the village disco by car or on foot in groups. When they go out to smoke, they talk loudly, roaring with laughter.

Ivan looks at the dance floor, his gaze detached. He has just come from there and sat down to rest a bit. At times, someone or another comes up to him to say hi or to crack a joke. Just now Nadia, his former classmate, is approaching.

“This is Oleh,” she introduces a friend. A tall, lean boy with black hair stretched out his hand in greeting.

Right, the story begins right here.

They start talking and after a few minutes they go outside where it’s quieter. Around the corner of the recreation center, someone is laughing loudly and shouting something. It is dark and smokey over there. Oleh Savchuk tells a story about a homeless Norwegian man with whom he shared the food he bought with his last of his money when he was hitchhiking around Scandinavia. He has already traveled to many countries. Ivan listens to his stories with excitement.

A few days later he went to Sosnivka for the first time for Oleh’s birthday.

In two months, they were practically best friends. One evening, drinking tea in the kitchen, they were talking “about the meaning of life.”

Oleh asked, “What’s your ‘ceiling’?”

“I want to see the world from different angles, not just from my window. I want to see the ocean. Not just buy a ticket to Lisbon, I want to get there on my own,” says Ivan.

For the rest of the evening, as daylight was fading they discussed how to make this happen.

“I know, I’ll go on horseback!” exclaimed Ivan.

This seemed like an awesome idea to both of them because he did a lot of riding. It would be a cool adventure—riding across Europe just to dismount their horses right on the beach, to feel the salty wind touch their faces, and exhale “at the edge of the world.”

The guys were determined to go. But when they shared this idea with their friend Sashko, it fell apart like a house of cards: “No way, dudes, I’m not going with you. Have you gone mad?”

Ivan stopped.

Off and Rolling

Soon, Oleh went to Iran and disappeared for a year and a half. But one day he called Ivan and said,“I know what we need. Get ready, I’m coming back in April, and we’re going to Lisbon.”

In the Persian country, the guy from Sosnivka first saw a hand-powered tricycle and knew they had to have it. Ivan’s transport would cost 2500 euros, making up a third of the total cost of the planned trip.

The money was provided by a Kyiv businessman. Ivan’s friends approached him, told him the story, and then went to Germany to purchase the tricycle.

Ivan’s 20th birthday was two weeks away. Oleh invited him to Sosnivka supposedly for the wedding of a mutual friend so he came for a few days.

When Oleh got home that day, Ivan was sitting in the living room reading a book on his old Kindle.

“Come on, let’s go to the river,” his friend interrupted.

It was a lazy day, and Ivan wanted to read more than swim, so he was quite slow. He turned off the e-book and unhurriedly looked for his belongings. Oleh kept rushing him.

“What’s the big hurry?” finally snapped Ivan.

“Come on!”

A few minutes later, they finally went outside. Oleh carried his friend down from the second floor in his arms, and, when the door to the building opened, Ivan squinted, not from the sunshine, but from the confetti. All his friends were there cheering. The crowd parted shouting “Dreams come true!” Ivan could only say, “Wow!”

Oleh helped him onto the tricycle to many cheers. Ivan had only seen how it worked in a video, so after his first uncertain movements nothing happened:

“Does it roll or not?” he said confused.

Suddenly, the wheel turned slightly and Ivan smiled with trepidation, “It does.”

People, not Cities

Ivan is sipping coffee in a Lviv coffee shop. People here know him and keep coming up to his table to say hello. But his mind is elsewhere.

“To say that I was shocked is an understatement,” he gesticulates and laughs cheerfully. “Those were all people who contributed to the purchase. That very moment I decided I would go. Because you can’t be afraid of your dreams. You get it?”

Until then, Ivan had never ridden a bike, and here he had to figure out how to both steer and power it by hand. He only had one month to learn.

“I didn’t have time to be afraid. I had nothing but desire, and it was so strong that I was ready to endure any and all difficulties.”

For a long time, Ivan’s mother did not believe that her son would go, so she made no efforts to dissuade him, but when he was given a bike, she panicked. They managed to convince her only when Ivan beat her on his hand tricycle while she was on a two-wheeler at a “public” training.

Five people went on the trip: Ivan on his tricycle, Sashko and Oleh, who took turns accompanying him on a two-wheeler, Anton, who shot and edited videos for the blog, and Olenka, who was responsible for social media. Ivan was always on his bike, while the rest of the team rode in the car that carried their tents, a gas cylinder, personal belongings, and equipment.

I had nothing but desire, and it was so strong that I was ready to endure any and all difficulties

Ivan says it is not cities that make trips, but the people you meet. Therefore, in each city where the On 3 Wheels team stopped, they got acquainted with the locals and Ukrainian diaspora, often thanks to the Lviv Regional State Administration. Once, thanks to their support, Ivan and his friends stayed on the fourth floor of the Ukrainian Embassy in Prague where ambassadors usually live until they find a permanent residence.

“We traveled a hundred kilometers to Prague without taking a break,” Ivan says. “We went up to the room and there was a floor-to-ceiling window. The next morning we woke up and they gave us 3500 korunas. For them it was nothing, but it meant a lot to us on the trip.”

Acquaintances helped too. For example, in Turin they stayed with a photographer whom Oleh had met in Iran, back when he was just toying with the idea of getting a tricycle. Sebastian arranged the most memorable club night of Ivan’s life: a dance party at a squat in a dilapidated church.

However, not everything was perfect. There would have been no finish on the shore on November 19, 2016, if Ivan had decided to return home in the Alps.

On the Brink

Mont Blanc is 4810 meters high. It is the highest mountain in Western Europe. Before crossing the Alps to warm Italy, the On 3 Wheels team decided to conquer it. They had to make it before the cold set in, so they were going fast. Going up the German French? mountains was hard, but the descent was another matter altogether. Ivan was cycling at 65 kilometers per hour. As he went, he was thinking that should he slip up, his friends would have a hard time scraping up what was left of him.

Ivan was going down the Autobahn between the autumn mountains. He ached all over, and, squinting into a headwind, he thought about how good it would be to be at home in Berezivka. He could see the figure of Oleh on a bicycle ahead of him. Ivan braced to overtake him, but made a mistake and his wheel caught Oleh’s. It happened in a split second: a sharp turn and Ivan found himself on the guardrail next to the ditch, his leg trapped. Motionless, he could only watch people stop and get out of their cars to help. After coming to his senses, Oleh joined them. Ivan looked at the asphalt and saw a trickle of translucent blood pooling in a reddish lake. “Why so much?” he was thinking while people were getting him out from the guardrail. When Ivan realized he was alive and death was not in the cards, he took a closer look: it was not blood, but water mixed with blood; the cap had come off his bottle, and the blood was coming from his scraped elbows.

Having recovered after the shock, the team stopped to have lunch. Ivan ate silently, trying to convince himself that it had been an accident.

“Shall we cycle on?” Oleh asked.

They did, of course. Half an hour, ten kilometers. Ivan started getting his speed back. This time he was sure that he would not make any childish mistakes. But on a turn his wheel rubbed against the curb. He braked suddenly to regain control, the rear wheels went up, and, fastened to the trike, he flipped over with his three-wheeler. He hit his head against the road, bruised his face, and started bleeding again.

“Well, you’ve done enough for today,” Oleh tried to make a joke. The friends headed to the nearest campsite.

Ivan couldn’t ride, or look his friends in the eyes, so he left the team and went to take a shower. With the main culprit gone, Oleh, Sashko, Olenka, and Anton held a powwow: should they continue? Ivan seemed to be on the brink.

While they talked, the warm water was running down Ivan’s body. His scraped elbows burned. Living in tents for three weeks, traveling a thousand kilometers—that’s no joke. Pictures kept emerging in his head: it was warm at home, there was no need to go anywhere, he had his own bed, freshly cooked meals, his family waiting for him. “Why have thrust yourself out of your comfort zone? Why prove to anyone how cool you are?” he could hear his inner voice over the noise of the running water.

Suddenly an outside sound made its way in. Sashko was knocking at the door. He awkwardly offered him the suggestion the rest of the group had came up with:

“Maybe tomorrow you’ll ride in the car?”

Ivan was silent. He knew getting in the car meant ending the trip. Behind the door, Sashko also stood and waited in silence.

Ivan imagined how he could hop on a plane from Vienna to Lviv. Here he is going from Lviv to Berezivka. He spends all his life at home, going to the regional center from time to time. He sits indoors thinking about the fourth floor of the Embassy in Prague as the greatest adventure of his life. The decisive argument was “Have I gotten the gang to come all this way to the Alps so I could fall twice and give up? If we stop, you can forget about your friendships.” Ivan turned off the water and told Sashko through the door, “If I wanted to go by car, I would have done so from the very beginning.”

ІІ. No Right to Fear

On 3 Wheels did cross the Alps and they were soon drinking homemade Italian wine in Dolceacqua. They faced no more problems and in due time, they reached to their destination, Cabo da Roca in Portugal. Ivan says that the ocean did not really impress him, and the trip, in fact, served another purpose. He was after the traveling itself, after freedom. And, having tried it once, he can’t stop himself. Upon returning, the team decided to contribute to developing accessibility in Ukraine.

Not being afraid of taking responsibility should become our generation’s motto

At first, they considered founding a charity for people with disabilities, but the team could not determine a clear course of action. Subsequently, they realized that they had found the answer to their question back while traveling around Europe. In Nice they had seen la Joëlette, a special wheelchair that allows disabled people to hike. The Joëlette costs 3500 euros.

They decided to raise money on the Spilnokosht internet fundraising platform. But Ivan received a call from the STB channel inviting him to take part in the TV show Surprise, Surprise! At the time, the team needed publicity, so Ivan agreed. However, On 3 Wheels received much more. In the show’s finale, they got the Joëlette as a gift. Three weeks later, they went on their first hike testing out the method on Ivan. He conquered Hoverla, Ukraine’s highest mountain, on June 1, 2017. Since then the team has already completed 22 hikes and has a waitlist for its third season. The team of five people has turned into a community organization that has brought together over 400 volunteers.

Usually, those who want to conquer a summit call on their own to make arrangements. The hike takes one day. During this time, they ascend the mountain, have a picnic, and make it back down to the bottom. The person with disabilities is accompanied by 10–12 volunteers and a friend or relative who can be relied upon in difficult or stressful situations. The team has a large van with equipment and everything they need. Usually sponsors help with these things.

The hike is arranged by Sashko Lutsyk, the same guy who talked Ivan out of going to Lisbon on horseback. He is responsible for both the equipment and the process of ascending itself. Ivan primarily deals with the media; he is the face of the organization.

So far, none of their hikes has failed. Ivan himself says that neither he nor Sashko has the right to fear. And that’s good because fear can help you hide from many things.

“It is impossible not to assume responsibility—this is how things are after 2014. Be it responsibility for the entire country or for one individual. If ours or any other organization stops giving a damn, pardon my French, we will cease being the changes in this country. Today when taking a shuttle bus I heard two women under 50 say that they did not need those accessible classes where they could earn so little money. It’s good that they will be able to make decisions for only a few more years. Not being afraid of taking responsibility should become our generation’s motto.”

ІІІ. Fair Play

Apart from volunteering, Ivan has a permanent job as a call center operator. Despite this, he still sometimes feels overprotected by his family. It is not too surprising—for 20 years he did not travel beyond Lviv on his own, so his activity still seems unusual. Besides, before the trip to the ocean, Ivan had generally seemed content with his comfort zone.

It was not until after he saw Europe that he realized that things could be different. He saw that people could wait for him to get on the bus instead of swearing. He saw that the subway in Madrid was convenient, and Valencia had no cobblestone roads, the reason why he has to take taxis in Lviv all the time. However, he still believes that Lviv is the most accessible city in Ukraine.

“Walking from the Rynok Square to the fire station you can quite simply die,” explains Ivan. “But the curbs are still not as high as in Dnipro, for example.”

If you want society to treat you in a normal way, you have to play by to its rules

Ivan does not want any social privileges—he believes that it is wrong to give people an easy time just because they have a disability.

“I advocate for healthy accessibility and direct communication on equal terms between different people. If you want society to treat you in a normal way, you have to play by to its rules. And I’m ready for that.”

Ivan does not forgive pity. He does not need help he doesn’t ask for. He does not need the language of tolerance if there aren’t even simple things like ramps.

“Disabled people are offended when they are called invalids, but it’s kind of stupid—if my friends and I can drink coffee and have a good time together, what difference does it make what they call me?”

To See Again

In 2018, the project I See! I Can! I Help! was launched in Kharkiv. Fifty sighted and blind participants took part in a tandem cycling trip. Volunteers were the eyes for each pair on a bike. They had to describe everything that was happening all around. Ivan spent most of his time with the organizers on the bus, but he of course also interacted with the participants.

Ivan described the Poltava Museum-Estate of Ivan Kotliarevsky, which they all visited together: whitewashed walls, wooden windows divided into four equal parts, dark shutters, three sectors of the wooden roof, tulips near a low fence, two gable windows, two chimneys. Describing the picture as it moves along the route is no easy task, neither is explaining where the threshold is, when and how someone is extending their hand for a handshake, accurately counting money, saying who has entered the room, what the weather is like, etc.

After Poltava, they went to Kremenchuk and Orlyk, and after a week living like this, Ivan arrived in the city of Dnipro. He started to understand some things. Another three weeks on the road and they got to Kherson. They were supposed to end there on Independence Day, after having ridden a thousand kilometers on tandem bikes.

Before entering the city, the participants formed a column. The last kilometers led to Freedom Square. The closer they got to the city center the more flags there were on the streets, the more billboards with greetings from politicians, the more people in traditional embroidered shirts. One final push and they got up onto the stage. TV cameras surrounded them while they sang the national anthem, listened to greetings, and shuffled around the stage while the organizers distributed the medals for participation.

After the journalists let them go and the police had departed, they could relax. The finish was for appearance’s sake, but the rally itself was much more than that.

“Yes, everything is fine,” Ivan says on the phone to his mom.

After he hung up, he realized he forgot to say something important—that he was so happy he could cry. Because he could see this world.

Can’t Help but Love

“Lisbon boosted my self-confidence as high as possible, whereas I See! I Can! I Help! made me realize how blessed I am by He Who puts ideas in my head. I do not know who He is—God, Allah, Buddha.”

Ivan knows that he is as lucky as can be. He wants everything to be as simple as possible and for people to be as good to each other as possible. He talks about it all the time.

“I can’t help but love what I do,” he says, stepping down from the stage.

Translated by Ali Kinsella.

[This publication was created with support of the Royal Norwegian Embassy in Ukraine. The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Norwegian government].

Have read to the end! What's next?

Next is a small request.

Building media in Ukraine is not an easy task. It requires special experience, knowledge and special resources. Literary reportage is also one of the most expensive genres of journalism. That's why we need your support.

We have no investors or "friendly politicians" - we’ve always been independent. The only dependence we would like to have is dependence on educated and caring readers. We invite you to support us on Patreon, so we could create more valuable things with your help.

Reports119

More