Adults

More than 90% of children in orphanages in Ukraine have living parents. Some are taken away by guardianship authorities in cases when their parents abuse alcohol or drugs or live below the poverty line. Other parents simply abandon their kids and somehow move on. There are also plenty of examples of mature adults who have chosen not to leave their children in the care of strangers when such a decision seemed to be the easiest. Yet, for the most part, these silent foundations of fragile childhood happiness go unnoticed. We would like to tell two stories about truly mature people.

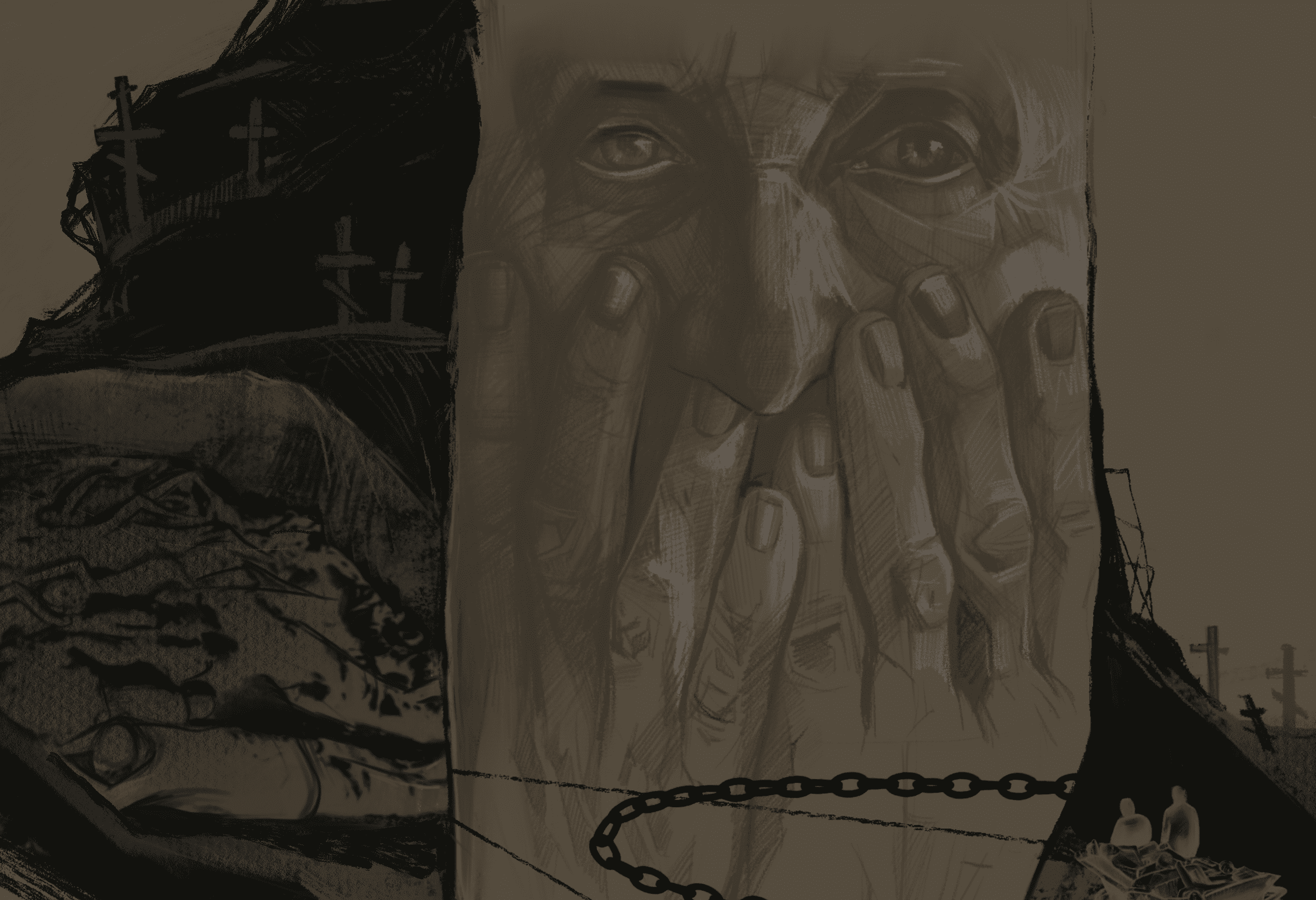

Father

57-year-old Oleksandr Fishych, a displaced single father from Donbas, was twice offered the chance to send his children away to boarding school. For the first time—in 2015, when he left his older Sasha and younger Sonia for nine months in a rehabilitation center in the village of Shevelivka in Kharkiv region and went away to make some money for the family. The second time—when he moved with his children to the village of Havrylivka in the Kyiv region.

“Both times social workers somehow found me,” Oleksandr says. “They said that I was too old, making too little, and that it would be much better for the children at a boarding school. I flatly refused.”

The kids heard everything and asked not to be taken away. There were very good conditions for displaced children in Shevelivka: a modern residential building, good food, daily transportation to school. Yet, none of this could replace the family for my children. Every time they called me, they would first of all ask: “Daddy, when will you take us away from here? When?”

While the man tells us about that painful question, his 10-year-old daughter Sofia is running around. Wearing a pink dress and white tights, the girl sits in an old chair with foam protruding in some places, swings her legs and watches the adult conversation. She brags that her father allows her and her brother to keep a dozen cats in the yard, and then hugs Oleksandr and blows a kiss.

“Because people in the village drown kittens,” she explains sadly. “And we save them! Although not everyone survives—only the strongest. Do not take a picture of this grey one, it lost an eye—it was sick, and it fell out. Take pictures of the rest, look how cute they are!”

14-year-old Sasha is also standing next to his father throughout the conversation. He is wearing black dress pants and a white, long-sleeved undersized shirt with sleeves treacherously riding up almost to the elbows. The lanky boy, like his sister, is the first to greet the strangers. He asks where we come from, why we are interested in their family, and what is new in Kyiv.

We are talking in the yard of a modest farmstead part of which Oleksandr rents for UAH 1,600 a month. The Fishych family house is located at the back of the yard: it is a one-story brick building, almost a hundred years old. Six more people live in the second building, located closer to the yard entrance: two women and four men, the tenants of three rooms with separate entrances. All of them are employed at a local poultry farm, where Oleksandr once worked.

The man came to the Kyiv region after he saw an ad in the newspaper; it said that the chicken factory in Havrylivka was looking for delivery workers. They promised a dormitory and a salary of UAH 3,500-5,000. The job was physically demanding, but he was willing to do any honest work to get his children back as soon as possible.

“We used to work in groups of 6-7 people. Every day, we had to deliver 300,000 chickens to the factory floors, where they would live until slaughter, and manually remove them from containers. It was hard, but I was constantly encouraging myself: “Come on, just a bit more. You can do it. For Sonia and Sasha, for your children. Come on.”

Oleksandr hardly says a word about his ex-wife Anna, who is 18 years his younger. He says the woman was a drinker back at home, in Luhansk region, but in 2014 her addiction took a turn for the worse. The couple divorced a year after the family fled the war to live with distant relatives in the Kharkiv region.

“I coded my wife twice, fought for her. The first time helped for a few years. And when Anna relapsed a second time, I realized that she wasn’t capable of raising our children. I filed for divorce. The court decided that Sasha and Sonia would live with me, and my ex-wife had to pay alimony. However, in the six years since the divorce, she has never helped us. She calls twice a year to congratulate the children on their birthdays. The other day she even said on the phone that she wanted to come back to us and be a family. It has been a month, she never came. I don’t think she will come. I do not care, but I am sorry for the kids—they love her and miss her, despite her drunkenness.”

Suggesting that he send his children to a boarding school, social workers bluntly told Oleksandr that he did not earn enough to support his daughter and son. NGOs seeking to reform Ukraine’s boarding school system explain that this is obvious discrimination. Daria Kasianova, Program Director of the SOS Children’s Villages Ukraine charitable foundation and Chair of the Ukrainian Child Rights Network, says the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC) has repeatedly reprimanded Ukraine over cases of the removal of children from their families for living in poverty.

“Have you ever noticed who goes to boarding schools?” Kasianova asks. “Often it is the people raised in such schools who send their own kids there. It is replication of orphancy, when entire dynasties end up living in boarding schools. After all, children raised outside a family, unfortunately, are not taught to love and do not understand the family model. It is difficult for such children to start their own families.”

However, this single father is dealing well with the imposed fear of lack of money. Because of the irregular schedule and low wages, he quit the poultry farm. While looking for another job, he collected and recycled glass containers, and also sold non-ferrous metals. He is still doing that to make some money, in addition to full-time work as a street cleaner.

“From the metal alone I can make about UAH 6,000 a month,” says Oleksandr, getting himself cozy in a chair in the middle of the yard. “At first I looked for it everywhere by hand, digging with a shovel, but now I have saved up for a cheap metal detector and the work is much easier. A few years ago I was also hired as a street cleaner in Havrylivka. In general, I can make up to UAH 10,000-12,000 a month. Our fellow villagers also help us—we never ask for it, but every now and then they would bring us potatoes or fruit. And when, due to quarantine, my children were not able to have free lunch at school, Dobrodiy Club from Kyiv, which helps children and families falling on hard times, brought us food packages.”

Despite my awkward questions about his ex-wife, fears and earnings, this strong man with work-worn hands and a high forehead does not ask his children to go into the house as matter of principle. He says that Sonia and Sasha know the whole truth about their family and the lives of the adults. Occasionally having to brush kittens off his knees, Oleksandr says the family also has a black shepherd dog nicknamed Wolf.

“That dog found us. One winter day, I saw him standing outside by our house, shaking with cold. It was not responding to any name. I took a closer look at him and said: “But you are a wolf!” And the dog perked up! He was almost jumping. So, I thought we should call him Wolf. The landlady forbade us from keeping the dog in the yard, so I had to put his kennel outside—all the way behind the garden. But still, Wolf has a great life! I work as a street cleaner, so I bring cheese, meat and milk for the dog and cats. This village is rich, and people throw away lots of good produce.”

The man is not ashamed to say that working as a street cleaner helps the animals, as well as himself and the children. He invites us inside his rented house: a corridor, a small kitchen and a room divided by plywood partitions into zones—for sleeping and relaxing, as well as a place where the kids can do their homework. Almost everything was brought from the landfill—even a sofa, a large closet and a TV set.

“Over the past year alone I have found a few thousand hryvnias in the garbage. And once I brought a chair to use it as firewood. I started chopping it up, and suddenly a wallet fell out of the lining. I opened it and found 100 dollars. Being a street cleaner is quite profitable. I am just talking about Havrylivka, but think about how much you can find in Kyiv or other big cities.”

Over the years, the man has collected so much discarded equipment that he keeps it in boxes and suitcases. In a shabby, once brown case, Oleksandr keeps hundreds of broken mobile phones. A reseller once offered to buy all of them for UAH 7 apiece, but the man refused—he says it is more profitable to sell them in the capital.

“Here, look, there are both touch-screen and push-button phones. There are broken ones, and there are some that look perfectly fine. I thought about getting some fixed so that the children could use them, but the price was too high—they said the phones looked fine, but were in fact waterlogged. I am generally in favor of digitalization. We are not rich people, but my children need to learn, so I put in the effort and bought them both tablets. They were constantly fighting when we only had one. And in quarantine they studied remotely, so they both had to have their own access to the internet.

Despite living in poverty, Oleksandr does not complain. He is focused on the children’s creative development. He has saved hundreds of books from a rural landfill: he gave some of them to the local community center, and left the rest to his children. In addition, Sasha attends paid street workout sessions on horizontal bars and obstacles. Sonia plans to go back to dancing classes, which she attended when she was studying at a school in the neighboring village of Syniak.

The son helps his father to collect firewood for the winter, and the daughter is responsible for cleaning—sweeping and dusting. The children have not yet thought about where they will study after school, but both are sure that when they grow up, they will take care of their old dad. Just like he takes care of them now.

“In general, harmony, respect, and mutual understanding reign in our family,” says the father as we leave. “The only thing I cannot give to my children, no matter how much I try, is their mother’s love. However, they are better off growing up with a single dad.”

Grandmother

Her son was hit by a car at the age of nine. As a result, he suffered a severe tracheal injury, lost the ability to speak and breathe on his own. Doctors performed a tracheostomy—he was breathing through a tube in his neck, until it accidentally got clogged. At 22, the young man suffocated.

The peonies have just faded in Natalia’s yard, while bright red roses and purple Hungarian irises have started blooming in their stead. In front of her old brick house in Bucha near Kyiv, there is a garden with vegetables and berries, where Yaroslav, her youngest, seven-year-old grandson and his friends are building a hut out of wooden boards.

At the end of 2017, Natalia became a guardian for Yaroslav, his 14-year-old sister Alina and 16-year-old brother Dmytro. Nine years after her son’s death, the woman also buried their mother, her middle daughter Lydia, who died at the age of 36.

“Now I have only the eldest daughter, 42-year-old Valentyna. She serves in the military and lives with her family in Hostomel. And Lydia died because she was grieving the loss of her husband. He was killed in a fight in 2013. My daughter faded away four years later—she suffered from kidney failure and had heart disease.”

Natalia Viktorivna, a short 67-year-old woman, tells her story while sitting on a chair next to the porch. Kashtan—a mongrel dog, which was brought home a few years ago by her granddaughter Alina—snuggles up at her feet. Natalia tells the dog to go away, nervously rubbing her hands. She says it is hard for her to think of her dead children.

As is usually the case, three years ago, before she applied for guardianship, social workers offered to send all her three grandchildren to boarding school. They tried to explain it in a nice way: “You have suffered a lot, you can visit them on the weekends and things will be better.” She refused because it is better for the children to be in a loving family.

According to the Director of the Ukrainian office of the Hope and Homes for Children International Charity Halyna Postoliuk, there are no protocols in Ukraine, whereby social workers must first offer families suffering hardship to send children away to boarding schools.

“Sometimes the directors of boarding schools use local social workers to look for children and receive more state funding,” says Postoliuk.

“Yet, most social workers in Ukraine sincerely believe that boarding schools are the place where children are supposedly protected and provided with everything they need. Most do not understand the profound damage caused by these institutions.”

As a result, they often do not realize that the main purpose of social services should be the opposite—to prevent children from ending up in boarding schools.

According to psychologist and psychotherapist Inga Palamarchuk, children who grow up outside the family circle lose basic trust in the world—the knowledge that the world will respond when you ask it for help. This affects not only younger children, but also teenagers: getting into boarding schools old enough to be fully aware of their surroundings, they may later reject society as a whole.

“Basic trust in the world is developed in early childhood,” Palamarchuk says. “It happens on a subconscious level. For example, a child starts crying: his or her mother approaches to find out what is wrong, and calms the child down. Instead, in a boarding school, a child crying for help may be ignored for a long time. Accustomed to the indifference of the world around them, such children find it difficult adapting to society.”

According to the psychologist, in a difficult situation, children tend to blame themselves first. Once in an orphanage, younger children will most likely think that they are the ones to blame. That they lost their parents because they misbehaved or did something wrong. This often leads to withdrawal, when even adult boarding school students believe that it is better to just keep quiet about their own problems.

Volunteer and activist Lina Deshvar, whose story was told by The Ukrainians a few years ago, grew up in an orphanage and emphasizes that the main thing is the desire to raise children and give them love, and not just leave the kid with his or her parents in spite of everything.

“If a child lives in a poor family, but at the same time, goes to a regular school, takes public transport, goes to the store to buy bread, he or she is adapting to society,” Deshvar says. “Instead, a child living in a boarding school is often not ready for independent living, even at the age of 15-17. I noticed this for myself and my friends who came out of boarding school at the age of 18-19. For example, no one taught us how to manage money—we had to learn it ourselves. And as to love and affection, in a boarding school you get no affection, you do not even know what it is. Children there will trust anyone who treats them well. A guest who came for two minutes, or brought a bicycle and talked to the child several times, will be depicted in their pictures as a friend.”

Natalia never regretted her decision to keep her grandchildren at home. When her intention became clear, social workers eventually helped the elderly woman gain custody. Nowadays, they occasionally help her take care of the youngest Yaroslav. While we are talking, the little rascal runs out into the yard, then runs back to his friends. Wearing a trendy cap with a large visor, he jumps through the bushes, then climbs a tree, and a few seconds later is back in the house: he opens the window and willingly poses for the camera.

“He’s a troublemaker,” the woman says. “He does not want to study, he is such a bully that sometimes he even hurts our dog, Kashtan. For some reason, Yaroslav has more respect for strangers. That is why I invite the social workers to talk to him—to explain why it is important to study and listen to his grandmother. Surprisingly, it works! After the talk, he starts to shape up: does his homework, stops hurting animals.”

Despite Natalia’s efforts, after their mother’s death, all three children, as expected, became withdrawn. They did not want to communicate with peers and rarely left the house. The grandmother inspired her grandchildren to live—as before, she continued to work in the garden, carried out small repairs in the house, and repeated to herself: “I have someone to live for. I have my babies.”

The loss of her own two children was not the first tragedy in Natalia Viktorivna’s life. The woman was widowed at the age of 39 and was left alone to take care of her three children. Her husband, Stepan, worked at a construction site, was exposed to too much sun, had a stroke and never came back home. A couple of years before that, Natalia became ill, and was told at the hospital: “You have a brain tumor, you need an emergency operation.”

“Honestly, I have no idea how I deserved all of this. Or why. Perhaps, this is how it was supposed to be. Fortunately, the tumor turned out to be benign. The surgery went smoothly. The only permanent effect of the illness is a stutter and tremor of the extremities. My relatives are now used to it, while strangers sometimes ask if it is because of stress.”

While we are talking, 14-year-old Alina washes the dishes in the kitchen, where we are all hiding from the heat. The girl is not very talkative. She wipes the plates and puts them in a row. She says she does not like to be photographed, and starts smiling as soon as we start talking about her grandmother.

“Grandma is so cool. She is patient with my awkward age and mood swings. Tries not to argue with me. Although my brothers and I clean and sometimes cook, my grandmother does most of the housework. Well, yes. . . Maybe we are a bit lazy. . . But otherwise, everything is fine!”

According to Natalia Viktorivna, the eldest Dmytro, whom we will not see because he is late visiting friends, is probably the only completely independent grandchild. The boy attends classes at a local college to become a confectioner. He has chosen the profession himself and wants to start working as soon as possible to help his family with money.

Currently, the grandmother and grandchildren live exclusively on government payouts: pension and child custody benefits. Money is tight, but enough for their basic needs: food, clothing, and supplies for education. The grandmother and Dmytro are the only members of the family having mobile phones, but everyone has their own room.

Two cats are sleeping peacefully in the small kitchen. Natalia Viktorivna is looking through a bunch of old photos. Some were taken only ten years ago, but the woman looks totally different there—she had sparkles in her eyes and no grey hair. She says she started looking drawn after her daughter’s death.

“There is no way I can imagine myself without grandchildren. And I do not understand people who abandon their kids. My life has never been simple. But my conscience has always been clear: I have never betrayed anyone.”

[This story was created with support of the Royal Norwegian Embassy in Ukraine. The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Norwegian government.]

Since the beginning of quarantine, Dobrodiy Club Charitable Foundation have provided food packages to over 7,000 vulnerable families across Ukraine. You can help the families who, in spite of financial difficulties, do not abandon their children, by making a donation at the foundation’s website.

Have read to the end! What's next?

Next is a small request.

Building media in Ukraine is not an easy task. It requires special experience, knowledge and special resources. Literary reportage is also one of the most expensive genres of journalism. That's why we need your support.

We have no investors or "friendly politicians" - we’ve always been independent. The only dependence we would like to have is dependence on educated and caring readers. We invite you to support us on Patreon, so we could create more valuable things with your help.

Reports119

More