Radioactive Tourism

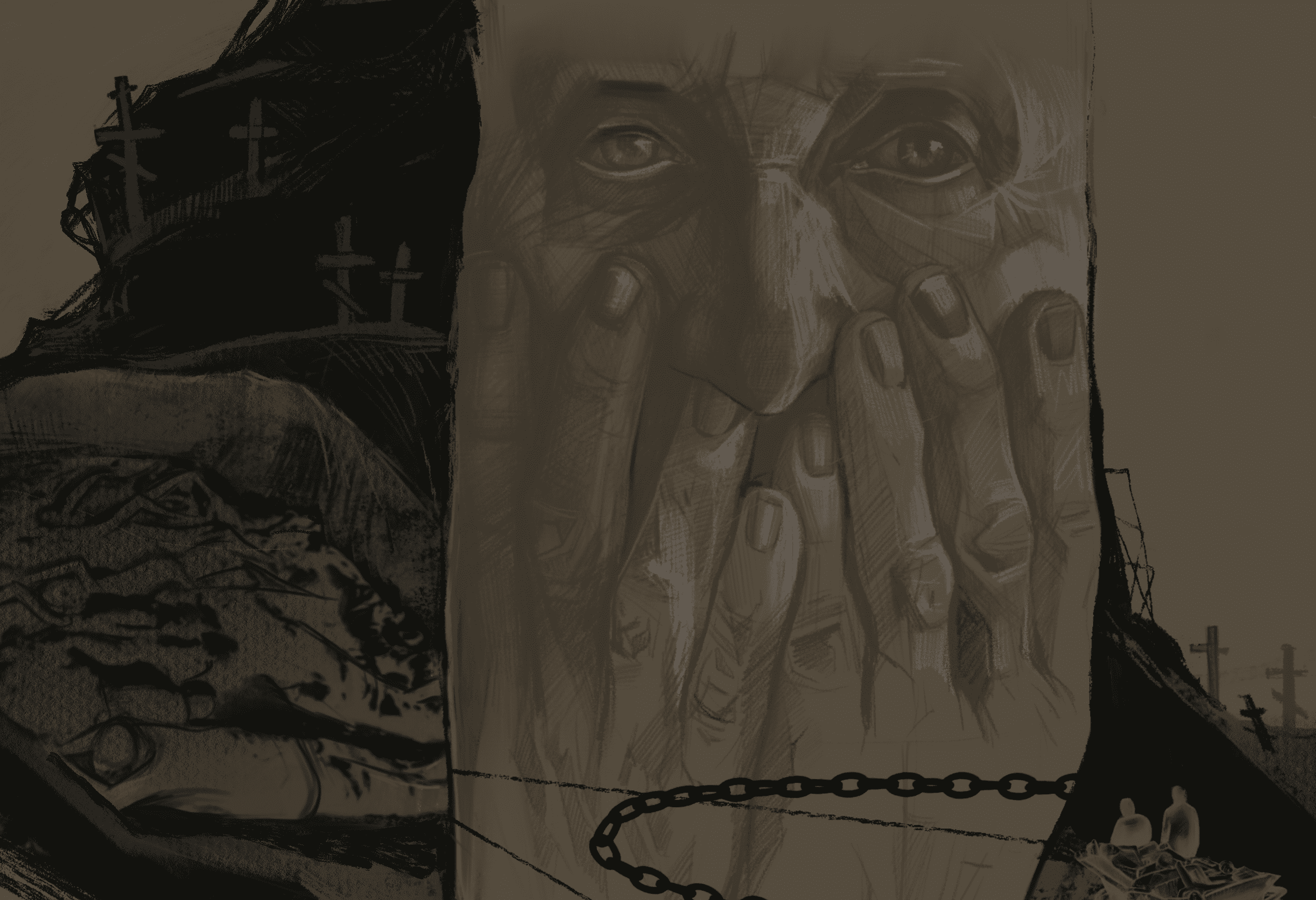

Everyone Has Their Own Fate, Their Own Evacuation

“If I had known, I would never in my life have gotten off that train. On Sunday April 27, 1986, we were put off at the Yaniv station, three kilometers from the fourth reactor. That day the radioactive cloud was already descending over the city. We were put off and the train went on to Moscow, where we were not allowed to enter. This was the last Khmelnytsky-Moscow train to go past the ChAES [Chornobyl Nuclear Power Plant].

“It’s difficult to tell this story because it’s like reliving it all over again. Grandpa was turning 60, so on Friday, April 25, we went to Shepetivka wish him a happy birthday. We returned on the same train on Sunday.

“We stepped out onto the platform with our bags and two children. It was hard to get through the crowd. There were people with sacks and a new police force in white uniforms everywhere. I kept hearing “evacuation,” and when I looked back, the train had already pulled away. At that time, no one knew anything. We had gotten off right by the reactor, but the police wouldn’t let us go home. They were saying, “The reactor has cracked, an explosion is expected.” But it had already happened a day earlier. They say that all the police in those white uniforms had received a mad dose of radiation and soon after died.

“We were trapped. We didn’t have our passports or any other documents with us. In those times we could travel by train without our documents. We had left everything at home, but we were forbidden from going there. My husband and I were 27. Tania was seven and a half and Aniuta was 22 months old. Aniuta was wearing sandals.

“Right after graduating from the architecture university in Kyiv, my husband and I were placed to Chornobyl. We arrived in August 1983. Everything was in bloom; there were a lot of roses in the city. At first we lived in a dormitory, but later they gave us a two-bedroom apartment. My husband worked in the construction of the final reactor and I worked at an information-computation center where I processed the documentation for the construction of the nuclear waste storage facility. The ChAES didn’t have one. Incidentally, this is one of the first violations.

“I think that we managed to survive because we had adapted—we had been swallowing small doses of radiation for years. At night we could often hear the power plant wheezing. This was the nuclear exhaust. The next day the streets of Prypiat would be white with soap bubbles. Back then we were so taken with this beautiful, clean city where the roses bloomed and they washed the streets with shampoo. But no one wondered why our streets always smelled so fresh. Or why people were treated to Finnish clothes and imported shoes. There was always enough of everything in Prypiat; we had no deficits.

“We stood at the train station for two and a half hours then. In ignorance. Aniuta wore her sandals to the end. A few years later, her joints started hurting. I blamed myself for this. My husband is on disability and 13 years ago I got cancer. None of us is healthy. Before we left, I washed the floor and did all the laundry. In a home that no one ever returned to. If I had known, I would have never in my life gotten off that train.”

Natalia, lived in Prypiat for three years

The Departure Stop

November 2018

Near the main gate to the exclusion zone, the Dytiatky checkpoint, the buses line up in four rows. Tourists have already been waiting for two hours to go on their Chornobyl tour. Thirty-two years after the greatest technogenic catastrophe of human history, people from all over the world come to Ukraine to see the ghost towns in the exclusion zone.

For some reason, the line isn’t moving, but the white minibuses are getting more and more. They say there are always lines like this on the weekends. The situation has especially gotten worse with the coming elections.

The tourists waste no time. They ask their guides, “What is the situation in Ukraine?” They are very surprised to hear there is a war in the country. Having satisfied their curiosity, they hurry off to the info station. There you can send a postcard for almost two euros, buy books, souvenirs, coveralls, or gas masks. A flat-screen TV in the corner shows a black-and-white slideshow of the disaster clean-up. A light jazz song is playing in the outdoor speakers. There’s a yellow freezer nearby: Chornobyl Ice Cream.

I head over to our group. The guide Serhii introduces me as an intern and asks me to read the safety rules. This is a private tour for 16 Spaniards. While I’m reading the rules, he gives everyone a kit that includes a bottle of water, tissues and wipes, and a dust mask.

“What are the masks for?” I ask.

“We just do it. Sometimes there are tourists who are very scared. So they put these masks on,” Serhii explains.

“Then why are they going?”

“Ha, we even get some who come but refuse to get off the bus.”

The Spaniards have come to Ukraine for three days. They are spending the semester on exchange in Lithuania. They decided to visit Ukraine because it is exotic and relatively close to Lithuania. They spent two days in Kyiv and one in Chornobyl.

“Listen, why did they give us these masks? Is it that dangerous?”

“Nah, you’ll just need to wash your clothes when you get home.”

A soldier with an agenda finally approaches our group. I read their last names, and one at a time the Spaniards offer him their opened passports. The document says, “purpose of visit: informative.” The soldier carefully reviews each passport’s series and number as well as the date of birth. Then the guide gets the agenda; every group gets one. This is an official permit that indicates just what tourists can see in the exclusion zone.

“Vaaamoos para dentro! (Let’s go inside. — R.)” the Spaniards joyfully exclaim after their two-hour wait.

We drive into the exclusion zone. The guide Serhii doesn’t react to their joy at all. He comes here five times a week—he has a full-time schedule. After six years, the zone bores him.

The Zone

“The guides often get burnt out. This is one of the reasons why I decided to leave. I started in 2015 when Chornobyl tourism was not yet widespread. The weather then was gloomy and gray. There were no leaves on the trees. I was given a map and told, “Lead.” Before that I had been in those places maybe three or four times. It was a little bit scary. Prypiat is big, uniform, and abandoned.

“I found the position on a job-search site. I had earlier gone as a tourist. The things I saw as a guide were different from what I saw as a tourist. Over time you develop a healthy cynicism to what’s happening. You can’t constantly be on edge. I read a lot of books about the Chornobyl disaster and then in the zone what I had imagined appeared before my eyes. When you spend a lot of time in the exclusion zone, other things start to bother you. For example, is there a third swimming pool in Prypiat, or where is the barbershop with mirrors, or the shop with the piano? We see the zone in our own way, so that it’s not so monotonous. You don’t become indifferent, your moods just change.

“One time I was again telling the story about the firefighters who fought the flames that night at the ChAES. We know these stories so well. You can deliver them to your audience with emotions while you’re thinking about something else. It was like that then. I was talking and when I lowered my eyes to look at the group, people were crying.

“‘It’s so tragic, so tragic,’ one of the guides said. And then she got in the car and sighed, ‘Ugh, Lordy.’ Sometimes there are instructions from the management to give fewer facts and instead manipulate emotions more. Very often you’re not supposed to talk about what’s happening in the country so people aren’t afraid of coming, since it’s mostly foreigners who go to the zone. First of all, it’s expensive for Ukrainians. Second of all, Ukrainians are more afraid. It’s most interesting when two worlds collide in one group. For example, a Pole and a Swede. The former you have to constantly force to put something else on in summer because you can’t just go in a t-shirt. But the Swede, for example, might put on a hazmat suit. We brand such people ‘lunies.’

“There are all kinds of tourists. Some are totally freaked out. Once there was a German who wrote his will before going to Chornobyl. But there are others who say, that we are just scaring them, that they know it’s safe. There are lots who have dreamed of going to Chornobyl for years. We have had marriage proposals in the zone. I once gave a tour to a couple from Chile. They flew in at night, we went on the tour, and then they flew back to Chile. They circled the whole globe to visit Chornobyl.

“People from countries with lots of nuclear power plants are very interested and always ask a lot of questions. For example, the French and the Japanese. But the questions are mostly stupid. The majority of tourists don’t understand where they’re going.

“You can’t go inside the apartment buildings or other structures. That’s an instruction from the Rules for Visiting the Exclusion Zone. Most of them are in a state of disrepair, there could be glass or manholes covered in leaves. But the management of the tourist agency I worked for got mad at us if we didn’t take the tourists into the buildings. They said we hadn’t done the whole thing then. But if guides get caught red-handed, their passes are taken away.

“Those who come for a few days spend the night in Chornobyl. There are two dormitory-like hotels. There are also bars in the city with weird names like Eternal Call. The hotel is called Ten because the zone around the ChAES has a ten-kilometer radius and curfew is at ten o’clock.

“If you come first thing in the morning before the police have assumed their post, you can climb the Duga, the former Soviet OTH radar for the early detection of intercontinental ballistic missiles. I was a bit scared—at 150 meters it’s halfway up the Eiffel tower, after all. But if the tourists say they want to, you’ve got no choice, otherwise they might leave a negative review or complain to the management.

“In general, this work isn’t dangerous. But there were all kinds of incidents. For example, in one of the buildings the floor gave out underneath me. Another time I got something radioactive on my coat and I couldn’t get through the detector. Once I accidentally entered a building, opened the door, and a racoon jumped out. It was at that moment that I thought, ‘What kind of job is this?’”

Volodymyr, worked as a guide in the exclusion zone for one and a half years

The Next Stop—In Time

We enter the 30-kilometer exclusion zone. The story of the disaster unfolds before us. Outside the window of the white marshrutka bus, the buildings extend in a chain. They are empty; they have no windows or doors. Their only residents are the trees that grow up through the buildings. Suddenly a plaza appears; in the thicket I can only identify a large star. Further on the thick forest hides the buildings.

New road signs and blue signposts alternate with ones that have lost their color over time. We cross a bridge from the side with the new road and the blue and yellow guardrail. On the other side, there is no road and the green barrier has countless cracks. Here and there cell phone service pops up and then disappears again. The past coexists with the present here.

We reach the ten-kilometer zone and pass the checkpoint. This time we don’t have to get off the bus. We head straight for lunch (due to the two-hour wait, Serhii had to change our route a little). But we have another stop along the road—the Chornobyl Nuclear Power Plant.

“Wow! Look how it shines!” one of the Spaniards shouts having seen the arch whose profiled roofing reflects the sun. Many of the buildings’ green and red roofs are made of the same material. Since 2016 such gray “roof” has been hiding the sarcophagus, which still breathes death. Under the sarcophagus is the fourth reactor, destroyed after the explosion.

The tourists get off the white minibus. While the driver and the guide smoke, the Spaniards take turns getting their picture taken against the background of the fourth reactor.

“What’s the level of radiation here?” a tan young man asks the guide while his friends are returning to the white bus.

“Ahh, your group rented two dosimeters,” Serhii remembers and hands him one of them. He uses the other to show how they work.

“If it shows three, that’s dangerous,” the guide clarifies. The young man concentrates on the dosimeter.

“Point 2!” he shouts. While we’re driving to the cafeteria, they all take turns listening to how the dosimeter whines and occasionally wheezes.

Before going into the cafeteria, they each pass through a detector that measures radiation. You have to place the palms on either side of the detector. You have to take and hold a deep breath and suddenly the “clean” light blinks on the detector. While the group plays with this latest attraction, the station workers ignore the detector and go through the entrance with no radiation control.

We go up to the second floor and see a cafeteria bathed in light. The group lines up near the buffet and Serhii explains in English what’s on today’s tourist menu: borshch, porridge, croquettes, salad, and pound cake.

Only the tourists are sitting at the tables lined up in groups. The workers often sit alone or in pairs. I am last in line reaching for the borshch when I suddenly realize there’s someone standing behind me.

“My name is Seriozha; I’m from Nikopol. It’s my 22nd day here,” a stocky man with light stubble says to me.

“I’m Ania. What have you been doing here that many days?”

“We are building a nuclear waste storage facility.”

“That’s dangerous work.”

“Alright, I thought you were American and I just wanted to touch you,” Seriozha smiles and walks away. I don’t get to say goodbye.

The Zone in My Blood

“The local workers are sick with a particular form of fatalism. There’s a contracting organization, Ukrtransbud, there. It’s a small construction company that won a contract for work in the zone. Today they get workers from all over Ukraine. In the Chernihiv region there’s no one to hire because they’ve all received an overdose of radiation. They can’t be hired back. People often can’t fulfill their contracts for this kind of work because they are overly exposed before it ends. So workers have thought up ways not to take their individual dosimeters or to wrap them in lead. All this for a salary of 7, but most often 5 thousand hryvnias ($200 to $280. — R.) every two weeks. The people who work under the arch near the sarcophagus where the level of radiation is very high do the same thing. Because if they get too high a dose, it nullifies their contracts. They are, in fact, biorobots.

“I know all this because I’m from Slavutych. My parents worked at the plant. We came in 1987 from Russia. After the clean-up the former employees of the power plant ran in all directions and it was difficult to drag them back. But they built the city of Slavutych for the ones they managed to get, offered them the best living conditions, and paid them triple salaries.

“I felt pulled to the zone. At first I came illegally. When you spend your whole life near the exclusion zone and your parents’ friends from the plant come over and are constantly talking about the zone, the ChAES, and radiation in the kitchen, you automatically start getting interested in it.

“It wasn’t totally by accident that I started working for one of the biggest tour operators. My friend worked for them as a guide and told me they were hiring. I, of course, agreed—the zone is in my blood. I liked it, got involved, and worked there for a long time. But I left after a disagreement with my coworkers. This kind of work is exhausting since you have to go practically every day. And working with people is complicated.

“But you have to remember that the zone is dangerous. No matter what some company might tell you, this is a zone of ecological disaster. What they show tourists and where they take them is dangerous, because no one is watching what the tourists are doing. The equipment for controlling doses is technologically obsolete and the standards are even worse.

“There is a radioactive spot in the village of Kopachi. It is invisible and can only be found with a dosimeter. The majority of guides go there every day to show this spot to tourists. Sometimes they reach out their hands or fingers for it. They take pictures with the invisible as if it were a joke. Okay, so one tourist goes up and takes a picture and nothing will happen to him, but the guide goes there all the time. That’s why a lot of them have beta burns on their hands that you wouldn’t even know about because they look like skin irritation. For example, I had an ulcer that wouldn’t heal for a long time because I kept measuring with my right hand. It’s utter sloppiness. Sure, there are detectors in Dytiaky that work, but they are outdated. The detector will of course squeal, but it’s not capable of a full examination. The side sensors don’t work, and how are you supposed to check your things? What if I accidentally got something on my bag in the zone?

“Yes, the levels of radiation have certainly fallen. But this is what makes it so dangerous. What’s most insidious is that everything seems to be okay. The central routes and the roads are relatively clean. But no one can guarantee that some idiot in a truck carrying radioactive material to be buried won’t drive through with an open tarp and spill it all onto the road.

“This happened to me. We were standing with tourists near the Prypiat memorial and I see a truck coming. I have no idea what it’s carrying because it was all under a tarp. And when he went past us, that tarp billowed in the wind. I had a dosimeter in my pocket and it started going crazy. This means that there was radioactive dust in the air. Thirty tourists breathed in that dust and then went home.”

Eugene, worked as a guide in the zone for six years

The “Life After Everything” Stop

Prypiat. We are wandering among vanished paths. Sometimes it seems like we’re in a forest. Suddenly, multistory buildings pop out one after another. They’re empty. Before us is life “after everything.” Wires that don’t lead anywhere. Things that don’t belong to anyone. Apartments that no one lives in. The apple trees weighed down with their fruits. It’s already November and no one has picked them. We were warned not to eat anything that grows in the zone, not to sit on the ground, not to touch trees. Not even to put our cameras on the ground.

The guide is in a hurry. We all run after him. We are trying not to look too long at anything, because if you fall behind, you get lost. And if you do stop for a moment, the silence rings in your ears. This doesn’t last long—only until another group of tourists steps out from a different path. The groups can be identified by their guides’ uniforms. One is wearing a hat with the radiation symbol; another is dressed in fatigues.

Ми всі у радіусі 500 метрів, чекаємо одне на одного, щоб нікого не загубити. Ті, хто поряд із Сергієм, встигають почути історії про Радянський Союз. Він час від часу гортає альбом із фотографіями «перед», ну а «після» ― перед нами. We all stay within 500 meters, waiting for each other so no one gets lost. The ones near Serhii get to hear stories about the Soviet Union. From time to time he flips through a “before” photoalbum—the “after” part is right in front of us.

“Dude, imagine how cool it would be to organize a festival here,” someone shares impressions of the spacious plaza with a towering rusty ferris wheel. The ferris wheel is tourists’ favorite place.

A High Price

“I believe it is an unhealthy curiosity. No one who survived it would go there on a tour. I remember that I was sick for some time before the accident. I constantly wanted to cry; it was like a stone was hanging from my soul. This is instinct, like with animals. I was constantly drawn to the announcement board with apartment swaps. But I was too late.

“It was a beautiful, warm day. There were lots of people out and about. It was my daughter’s birthday—April 26.

“I suddenly received a call from work and they told me that there were already five Roentgens in the city. I worked for the police. These 5Rs didn’t mean anything to me, so I called an engineer I knew who worked at the plant. He said that was the two-hour daily limit. He told me not to let the kids outside and to do a moist mopping.

“The kids are celebrating and I’m cleaning and cleaning; I can’t stop. My husband was working the nightshift. When he came home in the morning, he confirmed that there had been a fire in the night. I started begging him, ‘Let’s go, let’s go.’ But he said no. He said, ‘We do what the people do.’ And that he had work on Monday.

“I ran to the bus station because I wanted to take the children away. They blocked all our telephones; there was no connection. There weren’t any tickets at the counters either. The evacuation only started the next day. Saturday night into Sunday I finally managed to persuade my husband. He was convinced by the slamming of car doors. People were going outside wrapped in white sheets and packing their children into cars.

“There were two ways out of the city. At first we went to the one toward Belarus. But the gate was already down. They wouldn’t let us leave so that we didn’t spread the radiation. We went to the other exit and there was a new police force there. Ours had already been taken away to the hospital with fevers.

“There were a lot of cars in line and they weren’t letting anyone out. We waited until the end, until only our car was left. They still wouldn’t let us pass. For a long time I tried to appeal to the policeman’s feelings saying that you don’t just have to execute orders from above, you have to use your own head. But he didn’t react at all. I went on the attack, I said, ‘And what if I go around?’ He said, ‘I’ll shoot.’

“We were saved by a police car. I suspect that they were carrying alcohol, since there was a rumor in the city that you could save yourself that way. And they let us through. We drove into a fog that smelled like burning. We used the last of our money to get gas in Ivankiv. I was shaking. I kept on counting the buses. There were over a thousand. We realized they were evacuating our city.

“After that I only went back once. All that I wanted to grab was the sewing machine, but there was nothing left.”

Alla, lived in Prypiat from when it was founded in 1970 until 1986

The “Radioactive Daycare” Stop

The radiators in the daycare are partially cut off. The rooms are half empty, but who knows who has worked harder here—people or time. The daycare is located in the radioactive village of Kopachi, a mere four kilometers from the ChAES. There used to be a pine forest outside the city that excessive radiation turned red.

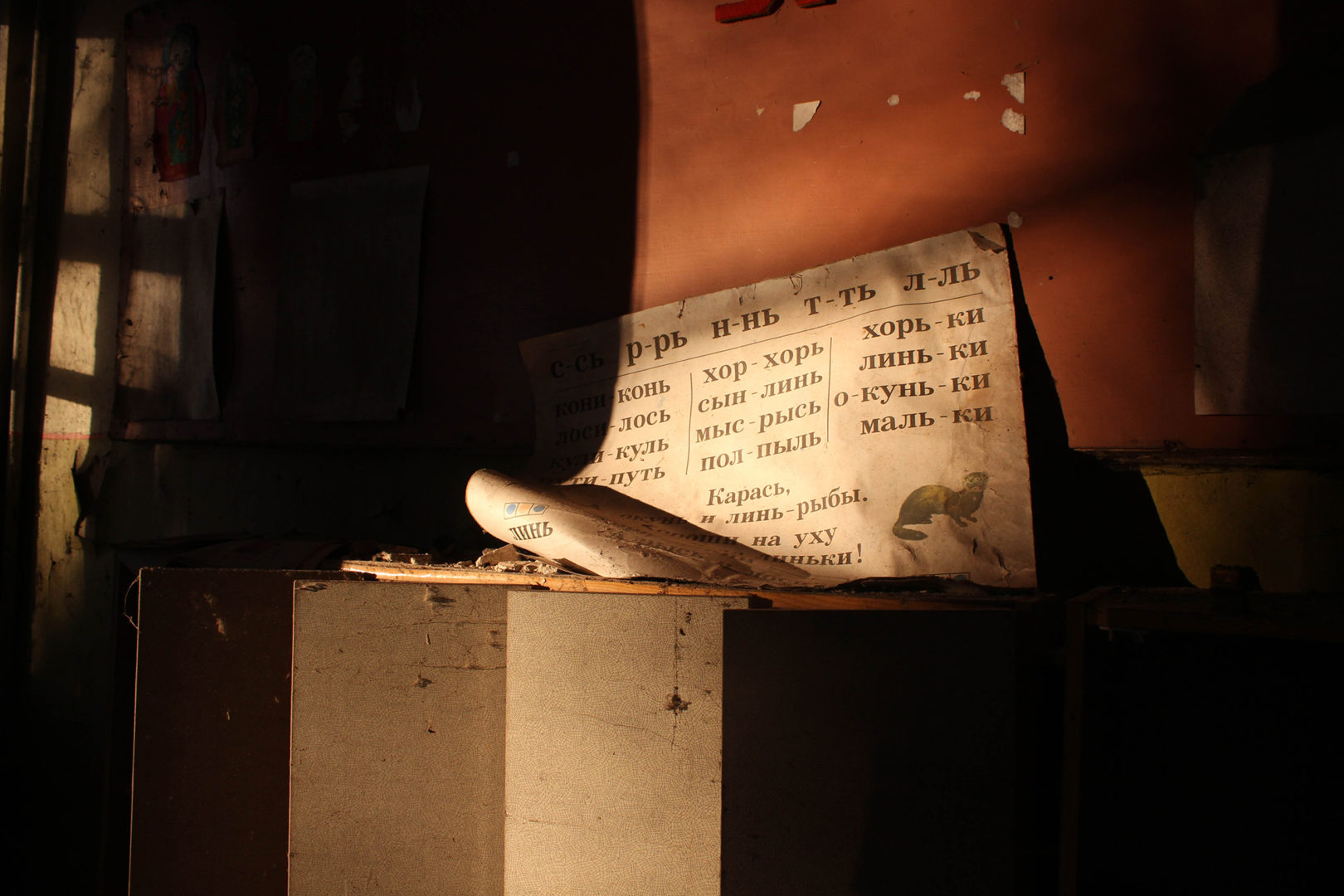

We are wandering among the rooms yellowed with time where children once played and learned. The arithmetic tables on the floor and the child-sized lockers speak to this. The kids who once kept their things here probably all already have their own kids. Today everything here is covered in dust.

There is a doll on the windowsill and the March 1986 issue of Barvinok on the floor. There are rows of rusty beds in the bedrooms; here and there is a pillow. The rooms are bathed in sunlight. The light falls on a bed with an open notebook. It is thick and for some reason open to a page with an explanatory note from a cook. There is a signature but no date.

The majority of the books are open; the toys have the lead roles in the most dramatic compositions. You can guess how many people come here every day. Right before we entered a group was coming out. But the walls whose green paint is curling into tubes tell a different story, one no one cares about.

It seems like this location has made the biggest impression on the Spaniards. The tan man with the dosimeter stops me.

“Did they all die right here?” he asks. I am surprised that he could ask such a question at nearly the last stop on our tour.

Droves That Pay

“The majority of tourists come in droves. I doubt anyone counts them. Earlier there was a tougher system in place. When I first started working, there were about 8000 a year. When it first exceeded 10,000, everyone was shocked. The growth in tourists started in 2015. Before the war, most companies were working in the Ukrainian and CIS markets. There was only one operator that worked with foreigners from other countries. After 2014, the situation in the market changed. One year attendance was 13 thousand, and the next year it was 30. One of the reasons was the popularization of tourism, as well as the anniversary in 2016 when they covered the sarcophagus with the arch. Then there was a total boom.

“I remember that in 2012 there were only weedend trips. They used large 40-person buses then. And at most there could be six buses. At that time, six people worked in the Center for Organizational-Technical and Information Support of the Exclusion Zone Administration (TsOTIZ), while now there are about 80. And sometimes they are not enough.

“The first tour was in 1998 or 1999 organized by the company SoloEast. The founder was from a village near the exclusion zone. He knew the right people and the trick’s done. At that time they were making out passes through the ChAES. Organized tours have been going on since 2006. The organization pripyat.com, which was founded by some former residents, started this. Once a tourist went with them, saw the potential in this, founded Chernobyl Tour, and started a chain reaction. This is how the other companies were hatched.

“In mid-2017, a tough war broke out when one of the companies started doing ‘next-day passes,’ even though the Rules for Visiting the Exclusion Zone indicate that a request to visit the zone must be sent a minimum of ten days before the tour.

“There are a lot of intricacies between cabinets. Right now these are droves that are bringing in money. No one knows where the money the tour operators are paying goes. According to the documents, it covers the state enterprises located on the territory of the exclusion zone. They are nonprofit which is why it is difficult to track anything. Tourism is bringing millions into the zone, but in fact nothing there is being renovated.

“Very few tour operator companies are registered in Ukraine. Most of them are in Europe. All the money the foreigners are paying goes there without taxes being paid here. Taxes are slightly lower there and there is the possibility of working with international payment systems. It scares foreigners, by the way, if they can’t pay for their tour with PayPal.

“I would strengthen the quotas and take safety more seriously. But it’s too late. It’s like a train that has already left the station and you’re still explaining how to lay the tracks. I think that tourism in the zone will exhaust itself. Because people are coming and want to see one thing, but they in fact see something else. People are told that it’s an abandoned place with no one at all. You show up at the checkpoint and there are a hundred other people excited just like you.

“Anyway, it has turned into mass tourism. People go there to take selfies with the ferris wheel. Some guides get in trouble if they don’t advertise the ‘expanded two-day tours’ or give too much information in one day than is planned for a one-day tour.

“At the same time, there is information that is never shared with the tourists. In Belarus, in the Homel region in particular, there are orphanages where disabled children who suffered in the Chornobyl disaster live. Tourists don’t hear this. They get to see the ferris wheel.

Anonymous employee of the exclusion zone

Final Stop

The passage through the detector at the Dytiaky checkpoint. After we have spent time in the zone, we must be tested to see how radioactive we are. Inhale. Clean. Exhale.

Part of the group has gone through control and is waiting on the street. The others are stuck in line. A few groups are leaving the zone at the same time. The Spaniards are taking their last group photo in front of the checkpoint.

“I’ll take you a fucking picture now!” suddenly rings out of the darkness.

The guide forgot to tell them that no pictures were allowed at the checkpoint. The scared Spaniards climb into the bus. Before the marshrutka plunges into sleep after a busy day, out of the darkness comes, “We wish you peace and harmony on the road.”

Translated by Ali Kinsella.

[This publication was created with support of the Royal Norwegian Embassy in Ukraine. The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Norwegian government].

Have read to the end! What's next?

Next is a small request.

Building media in Ukraine is not an easy task. It requires special experience, knowledge and special resources. Literary reportage is also one of the most expensive genres of journalism. That's why we need your support.

We have no investors or "friendly politicians" - we’ve always been independent. The only dependence we would like to have is dependence on educated and caring readers. We invite you to support us on Patreon, so we could create more valuable things with your help.

Reports119

More