The Stars of Kyrgyzstan

In schools of Kyrgyzstan, physics is still studied using textbooks issued when Valentyna Tereshkova went to space. However, the name of the first female astronaut hardly inspires young Kyrgyz girls; in some schools astronomy has been removed from the curriculum entirely. Exact sciences and space flights are not for women here. Gender still dictates a lot in this country: one’s profession and one’s role in family and society. Disrupting these traditions is “uiat,” which means shame.

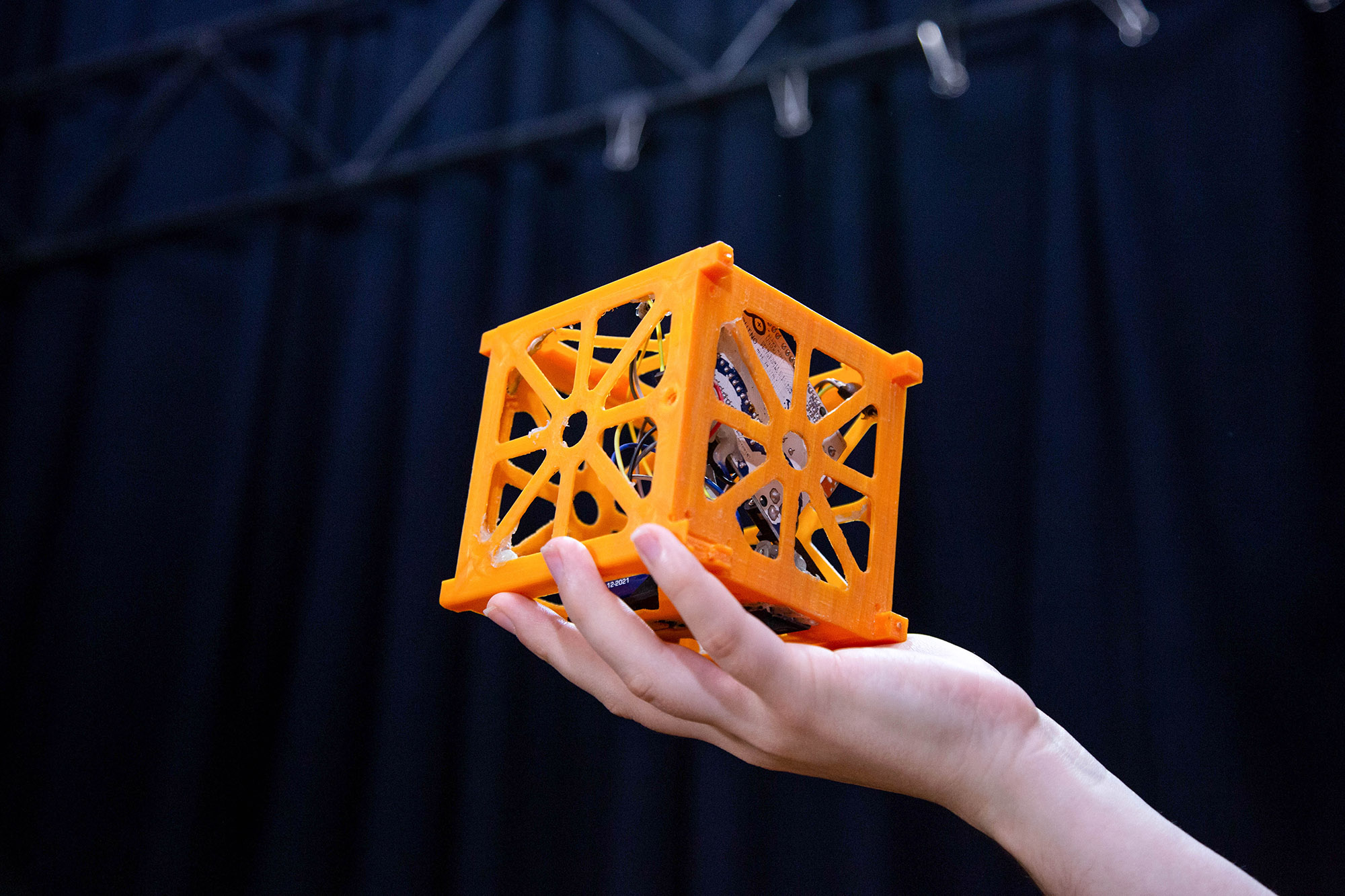

Meanwhile, as brides are still being kidnapped on the Kyrgyz streets, the pillars under the patriarchal system of this Asian country are being shaken by the Kloop online media which offers its own “space program.” Ten Kyrgyz girls are building and plan to launch into outer space the first satellite in the history of Kyrgyzstan, a cubic-shaped “cubesat” fitting in the palm of your hand.

Landed

Kyrgyz girls, like their Ukrainian counterparts, occasionally participate in feminist marches with similar slogans and demands. But there is a striking difference between the two countries. “Ala Kachuu” is literally translated as “grab and run” and refers to the traditional bride kidnapping in Kyrgyzstan. This custom is still alive; every seventeenth wedding in the country takes place without the bride’s consent. Usually, the kidnapped is locked up in the “groom’s” house until she agrees to marry him. She is persuaded, reminded of the traditions, and, if that doesn’t work, raped. After that, the girl cannot leave the “new home”, else she will “bring shame upon her family.”

Ala Kachuu is romanticized as a way of marrying against the will of one’s parents. It is an ancestral tradition. Several years ago, the custom was even used on Kyrgyz television to advertise real estate: at the beginning, a kidnapped girl tries to resist, but then, looking around and appreciating the beauty of her new home, she “falls in love.” There was also a TV series in the best traditions of soap operas: the main character is kidnapped by someone who doesn’t love her, but, given time and the principle of “marry first, and love will follow,” the story ends with strong feelings. In life, it happens differently. Last year, a kidnapper killed a 19-year-old girl right at the police station where she was filing a report on him.

Although Kyrgyz law prohibits kidnapping, only 28 cases have come to trial in the six years since the adoption of this prohibition. Only a few accused have been sentenced.

“Cultural” traditions are not limited to this. Every third woman in Central Asia experienced sexual abuse or discrimination. At the same time, male and female politicians in Kyrgyzstan still compare feminism to terrorism, and female leadership is called “bullshit.” There is no critical mass of people who would contradict them; girls in Kyrgyzstan are still forced to marry and shamed for relationships with foreigners, their virginity is treated as family property, and the best future offered to them is marriage and childbirth.

Kloop online media explain that they are tired of the rights of women in their country being so often violated and girls mostly being educated to be servants. The media, writing about politics, human rights, corruption and doing their own investigations, decided to influence the overall situation. Kloop is part of the investigative network. It has many international connections, and the co-founders often speak at conferences and forums abroad. At one of these conferences, the co-founder of Kloop Media, Bektur Iskander, met a NASA fellow, Alex McDonald. They spoke at the end of the conference, and Aleх encouraged Bektur to launch the first Kyrgyz space program. He said it would be cheap, and he would help with connections.

Launching the satellite will cost 100–150 thousand dollars. The campaign was financed by crowdfunding. The satellite is expected to be launched in 2020. McDonald’s offer proved to be a chance to show that girls in Kyrgyzstan have the right to make their dreams come true and, therefore, to choose how to live their lives.

Aizada, “moonlike”

Don’t wear short skirts. Don’t wear tight-fitting clothes. Don’t cut your hair. Don’t argue. Don’t laugh loudly. Don’t be emotional. Don’t swear. Keep quiet. Be modest. Be decent. Otherwise, uiat. Aizada, like most girls in Kyrgyzstan, was taught explicitly how to avoid putting shame upon her family. She would have to finish school and university, marry, and have children.

Her father dreamed that Aizada would become a doctor like his entire family, a successful dynasty in Bishkek. So returning home after working in England, he began to manage his daughter’s schooling. After the second grade he transferred her to a private school. When two more children were born, Aizada was moved back to a cheaper state school.

“Nobody ever asked what I like. Until the ninth grade I kept silent, and then I realized that something was wrong here.”

Aizada loved English, so she decided to choose a profession associated with it. Her mother learned about her interest first, reacted coldly and kept silent. But during one family night she told her husband. He shouted, “It’s not your call to make, eggheads!” Aizada cried all night long and ate leeks. That summer, she was moved to a new home in Bishkek and started attending the lyceum at the Kyrgyz State Medical Academy (KSMA).

Aizada, like most girls in Kyrgyzstan, was taught explicitly how to avoid putting shame upon her family. She would have to finish school and university, marry, and have children

The summer after her eleventh grade Aizada got a job as a waitress at a pizzeria. No one from her family ever did such work, because it is also uiat. Her father was angry and her aunts said that she was now “dirty,” because she worked in a place where people smoked and drank, and men called her over with a finger. But Aizada did not quit. She wanted at least some independence—yet in the fall she became a student at the KSMA.

“I did not have the right to choose myself, so I just went there not to fight with my parents. It was the best decision at the time.”

The best university, according to her parents, proved to be a school of hard knocks: the teachers did not respect the students, did not attend exams, forced the students to chase them for a good mark, and humiliated them. But as much as she wanted to leave, Aizada did not dare for a long time. Finally, after a year and a half, she went to the dean’s office to pick up her records. She had to pay 41,000 soms to the state ($600). Aizada borrowed the money from a cousin and became the first girl in the history of the university to quit.

At that time, her parents worked and lived in Russia. Aizada did not tell them what she had done for a long time, but she could not keep it a secret forever. It took her three days to put together a message to her father. When she finally sent it over WhatsApp, in reply she received half a year of silence.

“I didn’t know what to do with all the freedom, since during the years when my desires were oppressed I lost the ability to make my own decisions. At first, I wanted to choose a profession that would make others happy, but then I recalled that I had left the medical academy to pursue my own dreams.

Friends troll me that I’m collecting a Lego, but there will be time when I prove them wrong. Watching videos about space, I still wonder if our satellite will get up there. Will I really become a part of history?

Aizada lived with her older sister on the money they received from their mother. She began to learn Turkish, but failed to enter the linguistic faculty. After some consideration, she decided to try her hand at journalism. Based on placement exams, she could not get a scholarship, but this time she did not lose heart. To pay for at least part of the program, Aizada had sold ice cream for a month, working from ten to ten, earning 300 soms, or $4, a day.

She never regretted the decision to study journalism. One day she was having lunch at a cafe near the university, just two months after she started her classes, and overheard a conversation at the next table: “When will the second part of the investigation be ready?” From the very first remark, she understood that it was journalists talking. When one of them left, Aizada dared to speak to the woman who remained. The woman suggested Aizada to join her at an interview. The girl agreed, not even asking who she was scheduled to talk with. That was one of the turning points in her life. In the morning, she was still in class, and, in the evening, she interviewed a presidential candidate.

Aizada was persistent, and her new acquaintance entrusted her with transcribing records, calling up heroes and arranging meetings. Eventually, she was hired by an online media, but after a few months, feeling that she lacked the experience, Aizada quit and started studying harder.

One time, the editor in chief of Kloop independent media came to class. Aizada arrived early, so she was alone with the editor. While waiting for the rest of students, he told her about a new admission to the free Kloop journalism summer school. Aizada knew she had to snatch up this opportunity, and six months later she applied. It was no mistake. At the end of the course, she was invited to Kloop. Then, the satellite came into her life.

She is unvocal about her father: he is conservative, supports Putin, and tolerates no objections. Her mom says, “Satellite and Kyrgyzstan? Journalism? Hm!” They still see their daughter as an inactive, dependent high school student who never even picked her own clothes

She had known about the program since she started working for Kloop, but never understood what it was all about. Whatever it was, she still thought she was too bad at physics and math to sign up for a satellite construction.

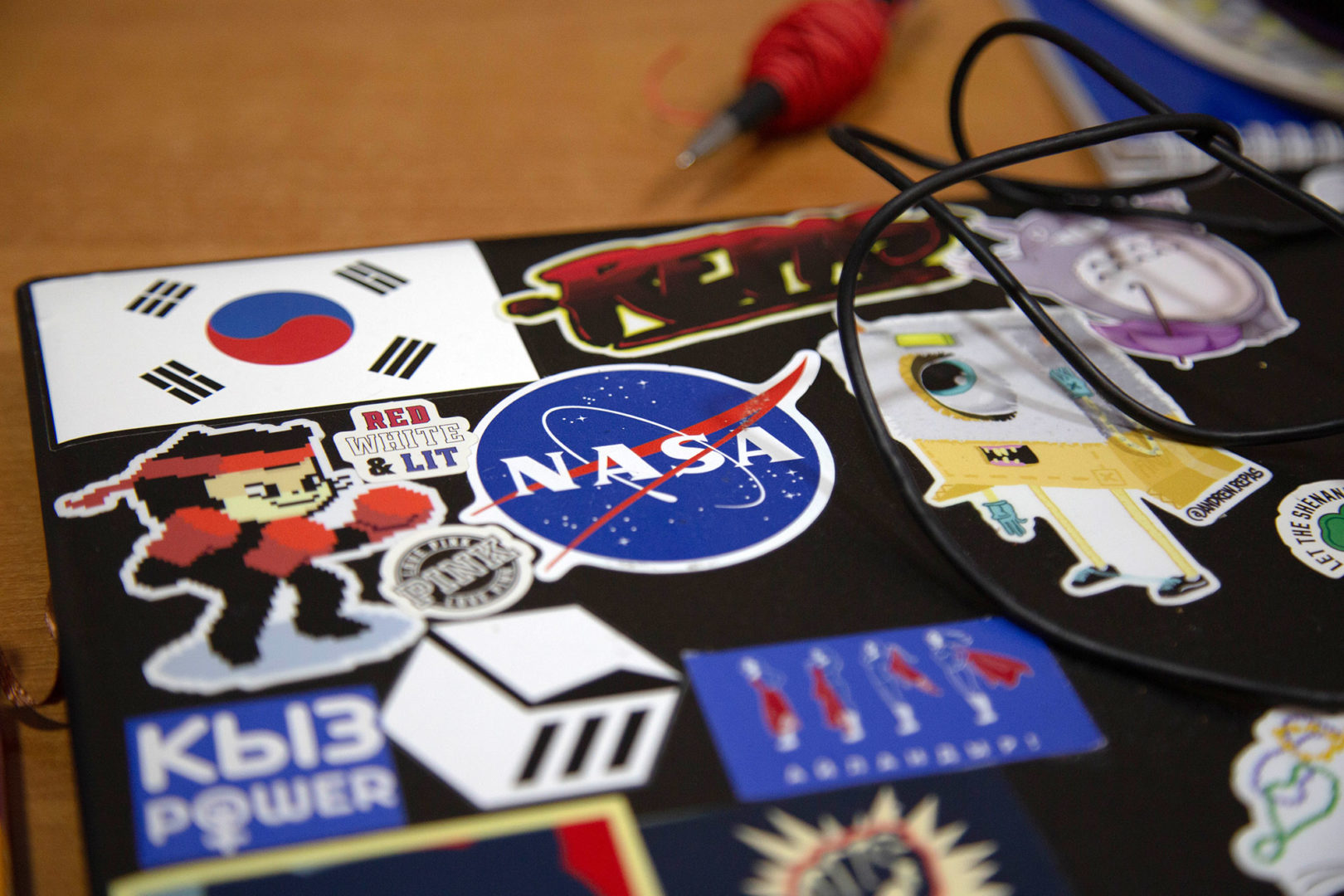

Basic courses in physics, programming and neural network writing proved difficult for her, so she did not bother with tasks much, making little of the project. But, when friends saw her photos on the program’s Facebook page and started asking questions, the girl sensed the responsibility. She spent more and more time studying and eventually got a scholarship.

Aizada’s parents do not support her. She is unvocal about her father: he is conservative, supports Putin, and tolerates no objections. Her mom says, “Satellite and Kyrgyzstan? Journalism? Hm!” They still see their daughter as an inactive, dependent high school student who never even picked her own clothes. Aizada does not try to explain how she has changed, because, in Kyrgyz families, it is not common to argue and express feelings.

“I still do not believe I can do it. Friends troll me that I’m collecting a Lego, but there will be time when I prove them wrong. Watching videos about space, I still wonder if our satellite will get up there. Will I really become a part of history?”

Behaim, “a mighty mistress”

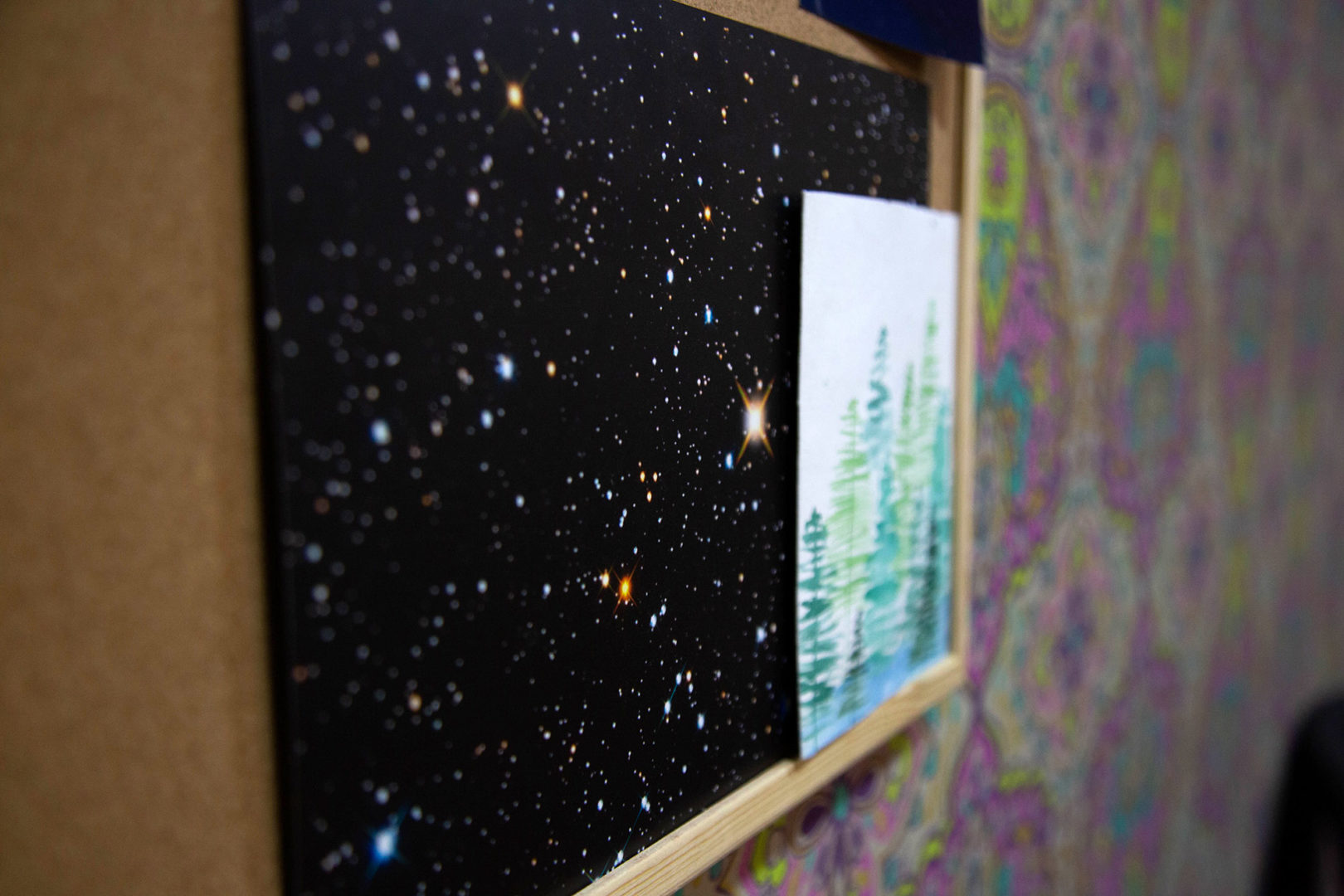

Ukraine and Kyrgyzstan are 4,500 kilometers apart, so the stars strewing their night sky are a bit different from what we are used to. Behaim, a 17-year-old girl, can neither explain the difference between the astrological maps in different parts of the world nor name a constellation. The school she will finish this year teaches no astronomy. Yet, Behaim is still dreaming of launching the satellite.

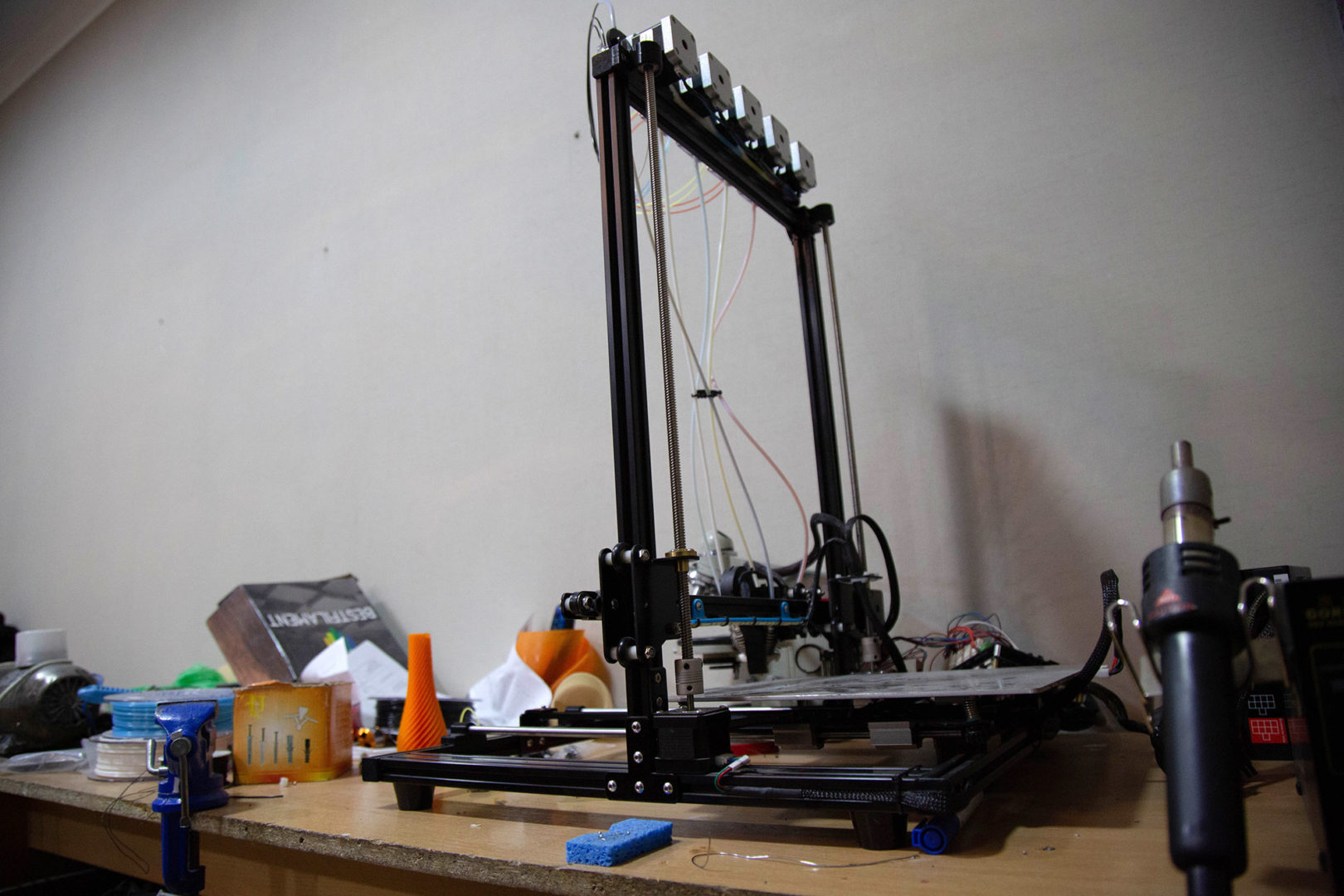

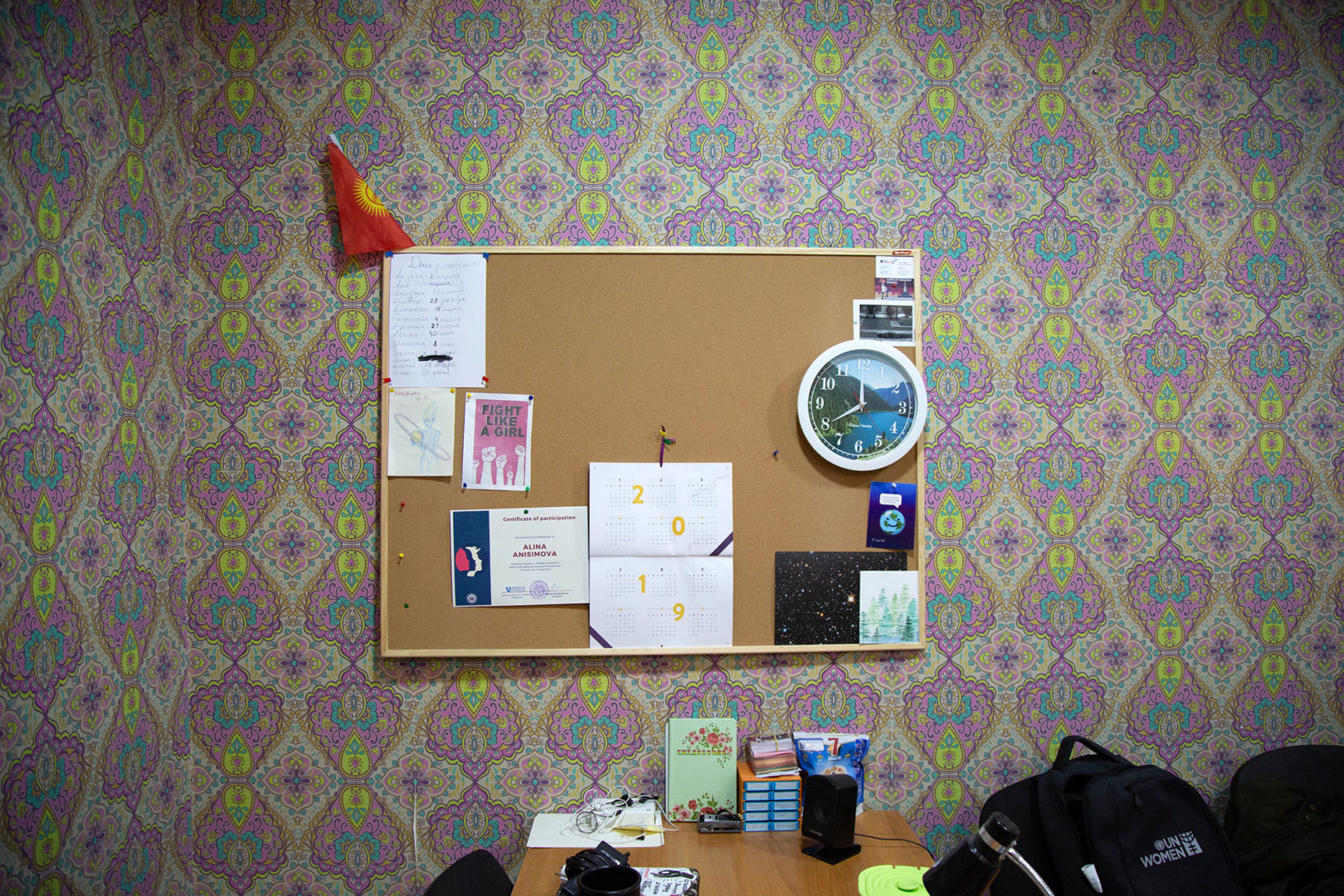

The project team now comprises ten satellite constructors. Together they study physics, mathematics, chemistry, and programming; simulate the behavior of objects in space; print test details on a 3D printer. The girls will not be launching a rocket or building a spacecraft. What may become the first satellite in the history of Kyrgyzstan is a cube-shaped device fitting in the palm of your hand. In the Kloop office, where the classes are held, the girls keep its prototype model. Behaim complains that it is often confused with the real one to be launched into space.

“We built this model in August and were very proud of it. But now, it’s a shame to even show it,” smiles the girl.

Kloop started its satellite building program in the spring of 2018. There were almost one hundred applicants, but, after the course, only a few girls stayed on.

“Usually such stories begin with people fascinated by space since childhood,” she skillfully solders a wire and looks up. “But it was different for me.”

If we knew more about Behaim’s grandfather, we would definitely write a separate essay about him. He had several daughters and one son, but, in a departure from local tradition, all children received an education. It is not clear how Behaim’s grandfather came to believe that a woman should be educated, but his children followed the example. Neither her mother nor Behaim were ever forbidden to study, despite such a choice is still considered strange in some places.

Behaim’s mother died early, so she lived with her father in a village in Jalal-Abad, the southern region of Kyrgyzstan. As the girl recalls, besides good and open people, there was nothing there

After her third grade, she moved to her uncle who lived in a city, a small, beautiful, one you can walk round. No education, but same kind and open people who will brand you for a pair of shorts. Four years later, Behaim moved to live with her aunt in Bishkek, and she lives there still.

Behaim speaks Russian but expressively calls herself “Kyrgyz.” Until the eighth grade, she entertained dreams of becoming the President of Kyrgyzstan or even the USA, before she saw a few films about space. She watched Hidden Figures on “colored” women at NASA and mused over her native Kyrgyzstan having no female astronaut. She decided to make a change, and her browser history got flooded with requests like “how to become an astronaut” or “the first female astronauts from different countries.” Then Behaim saw a post on Facebook about the recruitment of girls to the school of satellite construction.

“It felt like the universe suddenly turned around to make my dream come true.”

Behaim did not hesitate to apply, even though she had to google the answers to many questions. All her life, she had believed exact sciences were not her cup of tea.

In the class, the teachers of physics or mathematics talk only to boys, as if girls do not exist. Sometimes I intervene and argue, but more often I keep it to myself; I don’t want to hold back the class since I could never change the stereotypes of the teacher

Over the last year, the opposite has proven to be true. Every day, she attends the satellite construction classes. The project participants are tutored by invited teachers; some stuff they master on their own. New knowledge comes easier than she’d expected. At the same time, at these classes, she realized how good-for-nothing her school education was. No surprise, considering how dated the secondary education system is: textbooks from 1960s–1980s, just theory, no projects or labs. A mathematical pendulum is the top teaching guide. But the teachers are still convinced that exact sciences are not for girls.

“In the class, the teachers of physics or mathematics talk only to boys, as if girls do not exist. Sometimes I intervene and argue, but more often I keep it to myself; I don’t want to hold back the class since I could never change the stereotypes of the teacher.”

They have already found the company that will deliver the satellite to the International Space Station. The girls decided that the device would be operated by the Arduino microcontroller. Yet they had to reject the original idea of printing the cubesat on a 3D printer.

“It was naive to suppose that such a satellite would withstand the load of space. We will order parts from various companies. Of course, one can buy a ready-made kit, but we want no Lego; what we want is to assemble and launch a real satellite.”

This year, Behaim graduates from school and will take a break for the following year to prepare for entering a university abroad. She decided to fulfill her dream step by step, and the first one will be the launch of the satellite.

“Looking to the sky, I used to imagine how I would see the Earth from the ISS illuminator. At such moments my soul, it seemed, was leaving my body—it gave me shivers.”

Now Behaim has no time to romanticize. She studies physics.

Will it fly?

Almost a hundred people applied for the first enrollment. Now, ten girls are working on the project, four of them on a scholarship. Every day they spend no less than four hours studying physics, chemistry, and programming. Sometimes they learn how to operate hardware and the 3D printer and are consulted by the experts from NASA. Most of them are still schoolgirls, but a few have already graduated from university.

Indeed, there is a problem in Kyrgyzstan: girls cannot make their own choices. A girl interested in technical professions is criticized: ‘How will you care for your man?

It might seem too bold to call a nanosatellite collected from finished parts a “space program,” yet for almost thirty years of Kyrgyzstan’s independence no one has ever done anything like this. The girls are engaged in both technical and administrative work, organize classes on the basics of physics and engineering, and plan regional training camps. A girl with any level of knowledge can join their team after some training; as a matter of principle, boys are not allowed, because for them the road to such areas is already clear.

Aizada explains, “Indeed, there is a problem in Kyrgyzstan: girls cannot make their own choices. A girl interested in technical professions is criticized: ‘How will you care for your man?’ In big cities, it’s not so bad, but in the regions people live by different principles, let alone feminism. What we want is to inspire other girls by our example.”

Aizada confesses that only a year ago she began to openly admit that her views and principles are close to feminism. In Kyrgyzstan, many still consider this word a curse. Behaim agrees, interrupting her testing of the 3D-printer:

“I convince my classmates that feminism is not synonymous with man-hating. And they say that women are to blame themselves, because men would never humiliate self-sufficient women. I used to have the same stereotypes and convinced others I was no feminist. Now I’m not afraid to admit it—but not to my family.”

We want not only to make women more visible in science and technology but also to inspire girls to make their own choices and fight for the right to be themselves

Practically every girl from Aizada’s company was subjected to harassment or innuendos—in the canteen, on the street, on the bus. Not once she had it too, and remembers well the feeling of frustration and shame. A colleague once told her friend, “Don’t worry, it’s okay, it happened to me too.” It is this “okay” that worries Aizada the most.

She explains that total family control, contempt for feminism and all the harassment still exist because of social perception of women. Participants in the space program try to change the situation in their own way.

“We want not only to make women more visible in science and technology but also to inspire girls to make their own choices and fight for the right to be themselves,” Aizada says.

To spread the message, the satellite constructors speak at events and conferences. For example, in the informative panel on human rights, Aizada and Behaim talked about the satellite they worked on and the importance of dreams. Schoolgirls approached to thank them after the event. Behaim recalls a few words from her speech:

“I have a dream. I want to be useful and do something important. Although I never became an astronaut, I joined the team building a satellite, so my dream did come true, but in a different way. And when you do something in your field, it’s always fine—no matter if you’re only beginning to study physics or already building a spacecraft.”

[This publication was created with support of the Royal Norwegian Embassy in Ukraine. The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Norwegian government].

Have read to the end! What's next?

Next is a small request.

Building media in Ukraine is not an easy task. It requires special experience, knowledge and special resources. Literary reportage is also one of the most expensive genres of journalism. That's why we need your support.

We have no investors or "friendly politicians" - we’ve always been independent. The only dependence we would like to have is dependence on educated and caring readers. We invite you to support us on Patreon, so we could create more valuable things with your help.

Reports119

More